Richard Moore describes himself as “just a guy who wanted to help.”

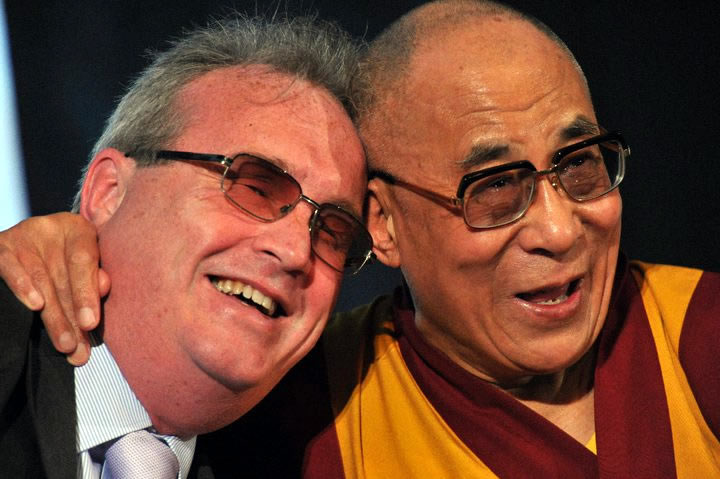

This is somehow funny coming from a man whom the Dalai Lama refers to as “my hero.”

Well known to the residents of Derry, Ireland, where we met last month, Richard Moore was shot at the age of 10 by a British solider on his way home from school. Taking a rubber bullet on the bridge of his nose, Richard lost his sight that day. His family’s, and his community’s story of forgiveness and triumph over this tragedy is a tale that Richard weaves and shares effortlessly, and yet so authentically.

How Richard’s story relates to the organization he founded, Children in Crossfire, and its work with local groups in sub-Saharan Africa is what I most wanted to talk about with him that day.

The value of community

Richard grew up in Creggan, Derry’s Catholic ghetto in the 1960s and 70s. People in his neighborhood were sealed in, living behind barricades made of rubble, broken pavement, burnt out cars and trucks, whatever would keep out the British forces. Richard describes this as a very tense time. He remembers the constant smell of smoke and CS gas in the air.

“Despite the problems that existed in Derry at the time, I come from a good community. I don’t believe that I grew up in a community of terrorists. My friends and family were peace-loving people.”

Despite the poverty, social and political upheaval of that time in Northern Ireland, opportunities provided to Richard by his family and community shaped him.

Richard’s father fought tirelessly for him to return to mainstream school. In those days integrated education wasn’t the norm. It was assumed that Richard would go to a school for blind children, which would have meant him having to leave home. Richard didn’t want to do this. His father singlehandedly approached teachers in the local schools for them to tutor Richard privately. Eventually Richard returned to the school where he attended before he had been shot. His father’s commitment and zeal to help him fulfill his education has stayed with him to this day.

“I realized children in Africa deserved that same opportunity,” Richard says.

“Losing my eyesight became a positive experience because of how the community came together to help me and my family. As a result of that coming together and support I received, what should have been a negative experience, turned out to be a positive one in my case.”

From charity to justice

The fact that this sense of community even exists in the most impoverished or conflict-ridden places in the world is often a figurative blind spot for many people as they get involved in global poverty.

“When I finally decided to start Children in Crossfire, I didn’t have a clue. At first I wanted to help ‘those poor Africans’,’’ explains Richard. “I saw it as a real charitable issue and all I wanted was to do something.”

He was heavily influenced by the Irish Peace and Justice organization, AFRI, which organized many campaigns throughout Ireland raising issues around the injustice of poverty. Richard started out working with the non-governmental organization, Concern Universal. The aid workers’ stories resonated with Richard, especially when they were talking about children.

“I became extremely emotional. Somewhere deep inside this spoke to my own experience.”

In 1992 AFRI organized a walk in Mississippi that reenacted the Choctaw ‘Trail of Tears,’ in which Richard took part. It was during this 240 mile walk that Richard decided to set up Children in Crossfire. In 1999 Richard made his first trip to a developing country when he visited Malawi. Richard describes his trip, in which he met with many local groups, as over and above the typical African “experience.”

“I discovered ‘they’ were happy. From my own experience growing up in Derry during the troubles, I should have known this, but I didn’t. I expected to see desperation, but instead I experienced benevolence and overt gratitude, which actually made me quite uncomfortable.”

“I went away from Malawi and my mind was like spaghetti junction, an L.A. motorway, with so many swirling thoughts and emotions…I couldn’t explain what I had experienced because I couldn’t understand it myself. Emotions at such a core level are very hard to articulate.”

I asked Richard what it was that transformed his emotional experience to expand his understanding of poverty as an issue of injustice.

“Exposure. Listening to others helped me see the people on the receiving end of help as not needy, but as holders of human rights,” he shares.

Today Children in Crossfire directly supports local organizations working with children on the ground in Tanzania, Ethiopia, and The Gambia in the areas of health, education and disability. Children in Crossfire also focuses on development education within Ireland. This enables those who support development work, financially or otherwise, to understand the reasons why people are in poverty. Also Richard believes that people in Northern Ireland can benefit enormously from seeing themselves in a global context.

“When we can approach our own community relations issues from a global perspective and look at our problems in relation to the rest of the world, we become ‘less’ Irish or British,” says Richard.

“For the ordinary person on the street here, the question is: ‘What do you think is your just right in terms of education, food, water, protection for you and your children? And then, do you think this is a basic right for children in Africa too?’”

However, Richard warns that there may also be a risk in making well-intentioned people think they’ve got it all wrong.

“There is a genuine wanting to do good in our lives. Therefore we’ve got to be careful in our approach with people with a charity mentality. Even if someone hasn’t yet thought through that far [to using a justice lens], there is a goodness there, a real goodness there, that we have to acknowledge.”

This acknowledgement of people’s goodness and meeting them “where they are” is a key approach to Children in Crossfire’s partnerships with local organizations in Africa as well.

“We don’t wave a magic wand. It’s just common sense to listen to what people need and support them in that.”

Richard and I discussed that doing aid work in this way [listening, providing responsive funding to local groups] is harder. Though worthwhile, it is slower. It requires more patience and self-awareness on the side of donors.

Richard shares, “There’s really a journey there. I get caught up and muddled in it sometimes.”

The balance of acknowledging people’s efforts on the ground, yet encouraging deeper questions is a hard one, especially while working in the context of the reality of historical inequities and old notions of inferiority.

“Here in Ireland, we know [that] better than most.” Richard reminds, “But you also have to take things from where they’re at. You can’t rectify the past just like I can’t get my eyesight back.”

The power of vulnerability

“I am vulnerable. I need people’s help everyday of my life, but I don’t think it’s a bad thing,” says Richard. “Asking for help sometimes seems like a weakness but it’s actually a sign of maturity…We’ve got to stop associating help with failure. ”

As we were talking on that Sunday morning, Richard’s assistant knew where we were and while on her walk (on her day off mind you), she stopped in just to see if she could assist him with anything. On the bus to Belfast from Derry recently, three strangers approached Richard to see if they could help him get where he was going in the city. These are just two of the countless experiences of compassion that Richard comes across on a daily basis, he says, because of his vulnerability.

“Maybe it’s wealth, our better lifestyles, which make us less dependent on each other these days in Ireland,” says Richard. “But people don’t need to have bullets flying over their heads or to live in abject poverty to be vulnerable.”

“Maybe more independent people don’t grasp the kindness that I get to experience,” he imparts. “If I could see, I wouldn’t experience that genuine human element [offers of assistance, physical contact/touch] every day. It puts me at the receiving end of such generosity and I love it.”

Richard and I discussed if transforming how we view vulnerability could also alter how we offer aid to communities in the developing world. Rather than seeing ourselves as conquering heroes of vulnerability through our assessments and interventions on behalf of “the poor,” Richard’s life and work demonstrates to me how aid work, grounded in compassion and interconnectedness with our own personal experiences, has the power to be transformative for everyone involved.

And that is why, like His Holiness, I’ll be counting Richard Moore among my heroes too.

***

Related Posts

An aid worker’s poetic journey

Sorry but it’s not YOUR project

Aid, Africa, Corruption and Colonialism: An Honest Conversation

I’m reminded of Ehon Chan’s campaign here in Australia, to challenge constructs of masculinity (with the intention of reducing the huge rates of young male suicide):

Soften The Fck Up!

http://goo.gl/jtA1R

Perhaps there’s a link that could be drawn here.

Nice post.