Andebo Pax Pascal shares his experience as an aid worker in Africa’s newest country in his second guest post. By examining beneficiaries’ place (or lack thereof) in two projects, he explores whether the development discourse has drifted into the abstract, beyond those he serves.

***

The idea of different categories of people–donors, government representatives, implementers, beneficiaries–interacting with one motive to improve the human lot is noble. But the internal dynamics of the system is another matter altogether, intriguing and yet baffling. The following two stories illustrate this, especially when it comes to how the beneficiaries or target group are treated.

***

At the end of a long day, I sit at the restaurant and overhear two fellow aid workers at the next table, Patrick and John*, discuss ideas about how information about the school block construction project should be shared with the beneficiaries.

John, the Programmes Officer, suggests that community representatives could be fully brought on board to plan and have access to all information (including funding amounts), which would also introduce the leaders to managing the school block project once the NGO has left. Patrick, the Project Administrator, argues that the policy of the organization does not allow him to disclose such budgetary/resource details to the community or their representatives, not even to the local government officials.

In any case, Patrick argues that the organization is going to finish a magnificent building that they could not afford by themselves and hand it over to the community. He further opines that even if the community has other ideas to suggest about the building project, these would have no room since, in essence, the beggar has no choice. Patrick reminds John that they are not employees of the local community, but rather are working for the NGO.

As I follow the discussion, I picture myself. Do I act in a two-faced manner when I deal with the beneficiaries? Are there moments in which I have to share information with them in a way that leads me to act superior, working merely as an agency representative guided by policy? If so, I convince myself that I am justified to do things this way. I have to follow policy. On a second thought, I also wonder whether I do these things to provide genuine service to the beneficiaries, or to protect my own position.

***

Charles* left his home country in the West to settle in South Sudan after the civil war in 2005. A typical do-gooder, he was driven by a need deep inside himself to alleviate human suffering. He chose to focus on orphans, those who had lost their parents during the conflict and would certainly need the hand of someone to take them through the challenges of growing up.

With the financial assistance of a few friends from his home country, Charles established an orphanage, gathering sixty five orphans, boys and girls of different ages. He first focused on having a roof over the orphans’ heads and fulfilling their basic human needs, including school attendance at the local primary and secondary schools. He then acquired some land outside town in order to help initiate a project in agriculture for producing food and tree-planting. The orphanage also supports a youth choir that includes the orphans and the children in the neighbouring community. The beginnings have been rather humble, though the few orphans I was able to interact with seem contented with what life has now accorded them.

Planning for the future, the management decided to build a more decent home which could eventually accommodate 150 orphans. By the standards of the existing building, it is already one of the few modern structures in the town. According to Charles, this building project was to be completed in three years, but had stalled due to the fact that the friends are faced with economic hardships.

I visited the orphanage with another aid worker, Peter, who had some contempt of Charles’ efforts. Apart from appreciating the support for the education of the orphans, he had many reservations about the fancy building, which in his opinion the orphans didn’t need. He also suspected that someone probably ran away with the money meant for finishing the building.

I found it difficult to make a judgment about Charles’ intentions, as well as Peter’s conclusions from our visit. For instance, was Charles merely following his own lofty aims of “saving children” in postwar South Sudan or did he just have the best interests of the orphans at heart? Was the orphanage benefiting the orphans in the long-term? Were the orphans even part of the planning process? Were Peter’s assertions based on core development principles or just personal opinion? I finally resolved that perhaps the best judge(s) in the matter could really only be the orphans themselves.

***

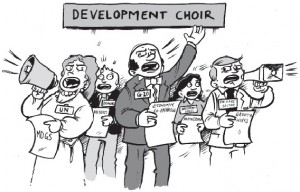

Were the attitudes, biases, stereotypes, values and visions reflected by John, Patrick, Charles or Peter in these two stories a true reflection of the beneficiaries’ position? How much should beneficiaries know about a project? To what extend should development experts make decisions in the project on behalf of the beneficiaries? Should they be considered as true participants or just end-users? Perhaps beneficiaries only exist in the aid system to balance an equation:

Aid x the principles/opinions of practitioners = Development (for beneficiaries)?

One thing I know for certain is that in development, people are involved at various stages and all are people with ideas, aspirations, dreams and values. How these are viewed by the ‘others’ within the aid structures is purely a matter of the attitudes, biases, stereotypes, values, etc. that individuals in the development industry carry with them. In the case of the beneficiaries, having a few of their representatives on board in the planning, implementing and monitoring of projects has huge advantages in transparency and accountability.

“We hold ourselves accountable to both those we seek to assist and those from whom we accept resources.” – Code of Conduct for the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement and NGOs in Disaster Relief, Principle 9.

Unfortunately accountability in most development projects aligns only with the power relations involved. Most aid organizations focus on upward accountability, such as reporting to donors, boards and head offices. The conventional vertical systems of accountability are themselves appropriate; however in many instances the beneficiaries are kept at bay. (For an alternative approach, see Mango’s Who Counts? Campaign for financial reporting to beneficiaries.) How can beneficiaries ensure basic accountability from NGOs, at least in the resources approved for their direct benefit?

***

Andebo Pax Pascal is from Arua, northwestern Uganda and is currently working with the Jesuit Refugee Service in Nimule, South Sudan, where they are implementing education programmes. He can be reached at: paxande@yahoo.co.uk.

*Names have been changed.

***

Related Posts

Searching for Closure: A Kony2012 Postscript

How to Work in Someone Else’s Country (A Book Review)

How to build strong relationships with grassroots organizations, Part 2 of 3

From Manish on LinkedIn:

Excellent article!! and I can very well understand feelings of Andebo. I guess the view and expressions are not dissimilar to other places .. many aid workers will agree with feelings of Andebo.

To the best of my learning and experience in various countries in Asia and africa with various international NGOs I have learned that we [iNGOs] have made our procedures so complex, we try so many things at the same time with out learning from similar efforts from others or surprisingly from our own organisations efforts we well.. so manager/workers are so focused on “paper work” or making paper trail right [under the name of accountability] we grossly miss many basic things.. especially local participation and doing right things in simplistic way.

I guess we need to go back to basic [I guess time of 80’s and 90’s where we had simple procedures, less paper work /especially no emails but still had high efficiency in delivering the results.]

This is very very complex matter and no easy solution available but the best way to start addressing these issues are :::: simplify, simplify and simplify….

and I am sure by doing that we will slowly arrive the solution where up ward and down ward accountability are in place, NGO code of conducts are religiously implied, responses are build upon local capacity, community led responses etc!!

I completely agree with these two stories. This is the scenario in most (if not 100%) humanitarian and development sectors. Despite the efforts made by IRC, Red cresent movement,SPHERE guideline, Humanitarian Accountability and Partnership (HAP) etc. most of the Aid agencies and development organizations including donors and governments, we are still struggling to ensure downwards accountability.

I wonder whether it is because of our lack of capacity to understand what we mean by downward accountability (accountability to who we serve), how to ensure and measure that or whether it is our lack of interest. I understand that it is not an easy task, and there are lots of challenges and practical issues need to be faced,but that are common in all the other works that we do. So that excuse does not count. So I tend to conclude that it is the lack of our (by us I mean the Aid agencies, development organizations, donors, govt, policy makers) interest. Though with the aid effectivness agenda, increasingly donors are putting emphasize on ensuring and demonstrating downwards accountability, at the end of the day, their reporting requirement, the implementation policies and guidelines talk more about upward accountability and very less about accountability to those we serve.

So, I think this high time for us to change our position from “Do gooders” to genuniely fullfill the needs and rights of the people we serve as well unite our voice as aid or develpoment workers to influence donor’s policies, reporting requirements to ensure that it Counts the benefits and the sustainable development in the lives of people, not just the money we spend and the work we do.

Thank you for sharing these two stories and publicly reflecting on the dynamics of development work Andebo. I appreciate and can empathise with your dilemma.

I only want to add that change perhaps needs to begin with language. If we keep referring to people as ‘beneficiaries’, then they will never truly be included in the decision-making process. It is easy to dismiss this as semantics, but language matters and affects how we frame, reference, design and think about problem-solving. If people continue to be ‘beneficiaries’, recipients of public goods and services, then why should we consider including in a participatory way. Afterall, when you give something to someone, you rarely bring them along and allow them to determine the budget, item and purpose of your gift. All you want is their gratitude.

Andebo, thank you so much for writing such a thought provoking post. You have written on a topic that I hope will inspire more conversation As a donor I always ask the question, in a variety of ways, ” who are you accountable to?” and I am amazed at how often I hear people say “the donors” instead of the community they are serving. I realize there must be some accountability to the donors but the community or partners should come first. This is not a business with shareholders at the top of the accountability food chain but about poverty alleviation as well as serving people and communities.

I believe that if a community is thoroughly consulted and seen as a partner in the relationship then this issue of “who do I actually serve” would not arise.

I agree to a certain degree with Mr. Rigby’s point about the language we use having an affect on how we think about problem solving but language doesn’t matter if the intention is to work “with” and not “for.”

Thanks to all of you for the comments and ideas. I agree with the challenges like the one Brendan has mentioned in the way to call the people we practice development with. How to term the relationship among the different stakeholders in the development process certainly determines how they are ranked. At one time I had a discussion about terming them ‘the people being served’. But again that, to me, reflects their lack of participation too.

Thanks for sharing Andebo. This type of discussion is definitely necessary in the development community. Time and time again it crops up, and on numerous occasions we are pointed towards the endless rhetoric on participatory methods…as mentioned above, language can impact upon what and how it is done. However, it seems intention is perhaps the most important thing here. Empty rhetoric on participation is meaningless and will continue to remain so if the intentions behind it are not to actually include the supposed participants or beneficiaries.

I think we’d all be kidding ourselves if we denied that at some point of our working lives we have had our moral conscience keeping us awake at night with such questions…

I don’t think it’s helpful to deploy metaphors of “up” and “down”. Let’s think instead of two groups of people, labelled donors and beneficiaries (not to mention consultants and implementing agencies… but let’s keep it simple.) BOTH of these groups have needs. Both want something from the other. Now they’re going to sit down and negotiate a deal, each in their own (perceived) interests.

Nor is it helpful to imagine that only donors have power. Every donor knows that it’s HARD to give away money, and that there’s more money around then there are suitable projects through which disburse them. If you’re project/NGO ticks all the boxes and knows how to disburse in an accountable way, then YOU have negotiating power.

Finally, I think it’s not helpful to imagine that there are true interests, or true needs: there are just interests and needs of various groups, each from their own perspective. Beneficiaries have their ideas; donors have their ideas. Nobody’s “right” because nobody has any kind of sure knowledge of what the future will bring. In relationship to each other, all they can do is negotiate a deal, thinking what they think, hearing what the other thinks, and trying to come to an agreement.

My preferred model: two parties want to negotiate a deal. The negotiation is horizontal: this stops you from PRESUMING power relationships. Each has power (whether they are aware of it or not: better to become aware, if you’re not already so); each is differently skilled at wielding that power. (Watch a donor go nuts when a ministry simply refuses to disburse at the agreed rate.) Each has differing ideas as to what the best outcome of the deal is. Now we’re going to have a human interaction.

The real question is: what knowledge and skills do each side need in order to come to the best, most productive, most enduring, most mutually beneficial deal they can?

Pingback: Lateral Accountability | Engineer Without Borders