We are celebrating Labor Day today in the United States, a day dedicated to the social and economic achievements of the everyday efforts of American workers. What better day to share my thoughts on a book I’ve been reading on the lives of us, the development laborers?

Inside the Everyday Lives of Development Workers: The Challenges and Futures of Aidland, edited by Anne-Meike Fechter and Heather Hindman and published by Kumarian Press, is an ethnographic exploration of the people who make up “Aidland.” It was very fitting to read today on Labor Day Hindman’s argument in Chapter 9 that the invisibility of employment policy to aid policy has led to a further depoliticizing of aid itself.

Inside the Everyday Lives of Development Workers: The Challenges and Futures of Aidland, edited by Anne-Meike Fechter and Heather Hindman and published by Kumarian Press, is an ethnographic exploration of the people who make up “Aidland.” It was very fitting to read today on Labor Day Hindman’s argument in Chapter 9 that the invisibility of employment policy to aid policy has led to a further depoliticizing of aid itself.

Tobias Denskus (a.k.a. @aidnography) in 2007 described Aidland as “multi-sited, multi-dimensional spaces of relationships that are linked to ‘development’ and its resources, people, organizations as well as the public and the private aspects of living, working and researching a powerful and pervasive phenomenon.” He cited and quoted Apthorpe and Eyben, those who coined the term, “Stepping into Aidland is like stepping off one planet into another, a virtual another, not that this means that it is any the less real to those who work in or depend on or are affected by it in other ways.” (For more perspectives on the discourse on Aidland, see this series from The Broker Online.)

I have not seen so many references to Escobar and Ferguson in one text since grad school, but it was a welcome break from the “solutions”-oriented texts I’m usually reading or writing in my aid job. In the book, Fechter and Hindman operate from an assumption that development practitioners are “the drivers of the development machine”—a perspective with which I tend to agree. (See here and here.) Determining how the work is structured influences the outcomes of development work.

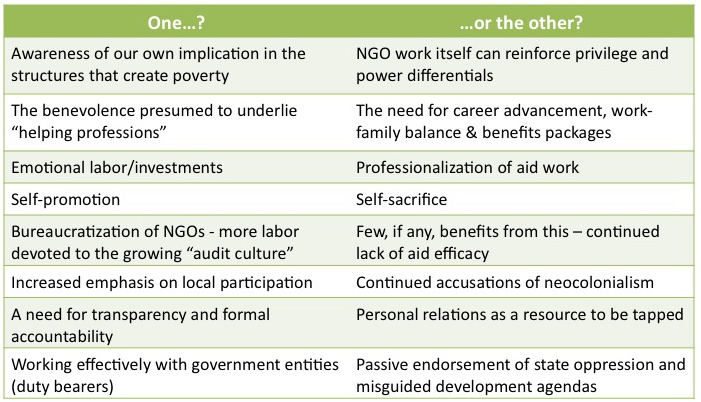

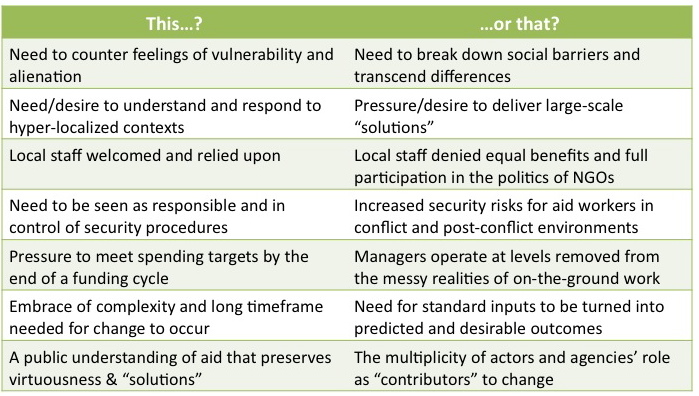

The nine authors in this volume demonstrate how Aidland is characterized conflicting relationships among various aspects of the “system” that development workers do indeed navigate on a personal level, on a daily basis with examples from Ghana, Madagascar, Indonesia, Macedonia, Cambodia, and Nepal. Below in the tables are just a few of these aspects that are highlighted and discussed in Everyday Lives, vacillating between altruism and egoism, pleasure and duty, and reason and emotion:

Those prone to dualistic thinking (“Yes, we can make a difference!”) are often the ones drawn to development work, and yet navigating the sector’s inherent complexities is exactly the kind of work that does not lend itself to this approach. Thus, I believe any notion of impact in international development will be achieved only through aid workers’ awareness, knowledge, and skill of how to accept this and work more effectively within this reality. To know ourselves better, we need people to help us see it.

Ambiguity abounds! Any book that helps us aid workers and do-gooders cultivate the sophistication needed to find our way among the great responsibility, privilege and burden of Aidland is welcome.

***

Related Posts

“That was scary”: Diary of a peackeeper in South Sudan

It’s all about the layers, Justin!

The best do-gooder advice I ever received

The westernized nature of the #socent industry

Thanks for an insightful review of the conundrum that is international development, always balancing expectations with results. Especially love the final paragraph.