Akhila Kolisetty is a blogger at Journeys toward Justice. (Shared here especially for @wmyeoh.)

The non-profit has become the status quo platform for international development and social change activism. But it hasn’t always been this way.

In the 1960s, radical movements for social change were challenging the capitalist status quo. Around the same time, foundations began increasingly forming as ways for the wealthy to support charitable giving while shielding their incomes from taxation. With the rise of foundations came the formation of the 501(c)(3) status regulated by the US federal government, since foundations could make tax-deductible donations to non-profits.

Early on, foundations began shaping radical organizing and Third World liberation movements into forms that would not challenge capitalism. Those who previously would have joined radical movements began forming non-profits due to the availability of funding; ultimately, movements have become co-opted into groups that do good, but are unable to challenge broader societal injustices and structures of oppression in our world.

Early on, foundations began shaping radical organizing and Third World liberation movements into forms that would not challenge capitalism. Those who previously would have joined radical movements began forming non-profits due to the availability of funding; ultimately, movements have become co-opted into groups that do good, but are unable to challenge broader societal injustices and structures of oppression in our world.

This is the phenomenon described in “The Revolution Will Not Be Funded: Beyond the Non-Profit Industrial Complex,” where social movements to challenge injustice and exploitation have been co-opted and transformed into more non-threatening forms that perpetuate the status quo.

My experience working and volunteering with a number of non-profits has shown me the tangible benefits they provide for the poor and marginalized worldwide. However, there have been myriad negative consequences of the “NGOization” of grassroots social movements:

1) Foundations allow non-profits to do work, but ultimately limit the work they do:

As Adjoa Florencia Jones de Almeida of Sista II Sista Collective writes in an essay:

“What has happened to the great civil rights and black power movements of the 1960s and 1970s? Where are the mass movements of today within this country? The short answer: They got funded. Social justice groups and organizations have become limited as they’ve been incorporated into the nonprofit model.”

Although foundation funding provides non-profits with the ability to function, the availability of funding ultimately molds the work of non-profits. First, social change groups are forced to market themselves in ways that will appeal to funders. That means packaging the group’s work neatly to target the specific priorities of foundations – even if that may not be the organization’s priority. That means using certain wording or complicated jargon to appeal to funders. Sometimes, it can even mean portraying the communities served as victims and voiceless, rather than with strength, agency and empowerment. Sometimes, it means that non-profits have to portray themselves as saviors to get funding.

Beyond marketing and communications, funding shapes the very essence of our work. Instead of focusing on movement building and strategies for radical change, many non-profits are spending much of their time seeking funding sources, applying to grants, and reporting on the effectiveness of their programs in a way that appeals to funders. Time and energy is spent on fulfilling benchmarks and reaching indicators that foundations seek, rather than on broader social justice movement building – which may not lead to immediate results, and is thus considered “ineffective” by many funders.

2) We are no longer accountable to the poor and marginalized.

As de Almeida writes:

“We as activists are no longer accountable to our constituents or members because we don’t depend on them for our existence. Instead, we’ve become primarily accountable to public and private foundations as we try to prove to them that we are still relevant and efficient and thus worthy of continued funding.”

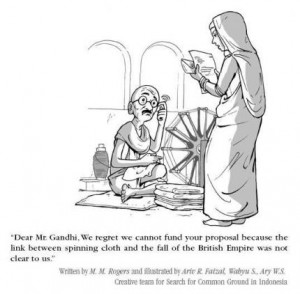

Indeed, foundations have their own priorities and their own agendas. Many foundations refuse to fund organizations that get involved in any sort of “lobbying” or political advocacy. But sometimes, political advocacy is needed to actually change things on a large scale. Some foundations ask non-profits to add more “innovative” programs to their proposals – or will suggest changes to proposed programs based on what funders feel is their current “priority area.” Simply doing what you believe is needed is not enough: you are limited, guided, and pressurized by the preferences and priorities of the foundations themselves.

Indeed, foundations have their own priorities and their own agendas. Many foundations refuse to fund organizations that get involved in any sort of “lobbying” or political advocacy. But sometimes, political advocacy is needed to actually change things on a large scale. Some foundations ask non-profits to add more “innovative” programs to their proposals – or will suggest changes to proposed programs based on what funders feel is their current “priority area.” Simply doing what you believe is needed is not enough: you are limited, guided, and pressurized by the preferences and priorities of the foundations themselves.

Drawn to the allure of millions of dollars of donor money, small non-profits cave in and tailor their very programs to what foundations are hoping to fund. Instead of doing what they really feel is needed, or what the poor and oppressed groups they serve are demanding, non-profits start programs they believe that foundations will fund. They figure that some money and recognition is better than none at all – so they completely shift themselves accordingly.

They are no longer truly accountable to constituents, beneficiaries or the communities they serve; instead, they cater to the needs of funders and donors. Non-profits, too, have thus succumbed to the idea that “money is power.”

3) Non-profits are taking the role of the state as essential services are being ‘NGOized’

Due to the plentiful foundation funding for programs – both domestically and internationally – related to health, education, mental health, legal aid, housing, food, water, emergency shelter, nutrition, and sanitation (among others), NGOs and international aid agencies have began to provide a range of basic services. Especially internationally, international development organizations have essentially begun to overtake the state by providing everything from emergency disaster relief to long-term healthcare, education, and housing.

Many of these programs should indeed be provided by the state. Governments have obligations to dedicate their budgets to improving and protecting the basic human rights of their citizens. While aid agencies and non-profits can and certainly should fill gaps, they should not take the role of the state. Besides, the proliferation of NGO and foundation funding may even serve to weaken the state. In particular, governments might have less incentive to really invest in these essential services if they feel the job is already being done by non-profits.

4) We are encouraged to compete, rather than collaborate.

As we search for foundation funding, non-profits increasingly find themselves competing with similar groups for money – rather than collaborating. Amara H. Pérez of Sisters in Action for Power writes:

“In the “movement market,” organizations competing for limited funding are, most commonly, similar groups doing similar work across the country. Not only does the movement market encourage organizations to focus solely on building and funding their own work, it can create uncomfortable and competitive relationships between groups most alike—chipping away at any semblance of a movement-building culture.”

I have experienced this personally. I have seen non-profit leaders and activists put their own organization first – even if it means putting a fellow non-profit down, refusing to share resources or knowledge, criticizing similar organizations, or sabotaging another group’s ability to get funding. Not only does competition for scarce resources prevent collaboration and movement building, but it actively encourages tearing down fellow activists to further one’s own cause.

5) We now have so many employees, but too few revolutionaries.

As de Almeida wrote:

“Would the Zapatistas in Chiapas or the Landless Workers Movement members in Brazil have been able to develop their radical autonomous societies if they had been paid to attend meetings and to occupy land? If these mass movements had been their jobs, it would have been very easy to stop them by merely threatening to pull their paychecks.

Nowadays, many people work for a salary rather than because they truly believe in the movement. We now have more employees, but fewer people willing to dedicate themselves to a true struggle for social justice. Getting paid can change the way we operate; we start expecting a salary and become comfortable, less likely to step out of a comfort zone or truly challenge unjust systems. We are less likely to take to the streets or do whatever it takes to fight injustice. We start seeing this as a “non-profit career” and seek to develop ourselves professionally. We are less likely to do unpaid work, and we become less likely to sacrifice if the movement demands it.

Some of the most incredible movements have risen from groups of people working together, building something out of nothing, and engaging in radical activism that challenged the status quo – for free. The largest movement builders on our planet – from Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr. to Wangari Maathai and the South African shack dwellers – did not exactly do it for the pay.

Some of the most incredible movements have risen from groups of people working together, building something out of nothing, and engaging in radical activism that challenged the status quo – for free. The largest movement builders on our planet – from Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr. to Wangari Maathai and the South African shack dwellers – did not exactly do it for the pay.

What is the way forward?

Undeniably, the work of non-profits and foundations has made a difference in reducing poverty, advancing human rights discourse, and saving millions of lives over the past few decades.

But going forward, we must reimagine this dominant model of social change and create one that can more effectively challenge exploitative social and economic structures. This is a tall order, and not an easy task. But it begins with small steps. As we learn from the revolutions sparked across the Middle East, change is not easy and carries many costs. It may require going beyond a traditional non-profit model, sitting in air-conditioned boardrooms while writing proposals and logframes that wax poetic about the poor.

There are many steps forward we can take:

We can: start accepting funds on our own terms, with the alternative being non-compliance and boycotts of foundation money.

We can: refuse to accept money from foundations that don’t share our values, and from organizations that try to limit or change our work.

We can: start from the needs of our communities, and instead organize and crowdfund the money we need, without strings attached.

We can: choose hybrid models such as social enterprises, where our constituents themselves are our customers, and where we can harness market forces to fund radical social justice movements.

We can: join hands and work together to better align the priorities of foundations and donors with what we know are the needs of the people we serve.

We can: keep speaking of our communities in ways that empower rather than victimize, provide greater opportunities for marginalized communities to speak out themselves, and lead the charge for greater collaboration.

We can: build organizations – giving circles – and foundations! – that are led by the poor, minorities, and the oppressed.

We can: organize, mobilize, and brainstorm ways to challenge the status quo without writing a proposal first.

We can: show our commitment by organizing for radical change on the side – for free.

We can: begin fighting the non-profit industrial complex, but only if we hold on to – and fight for – our values within this movement.

***

Akhila Kolisetty is a student at Harvard Law School. She studied Economics and Political Science at Northwestern University and the London School of Economics, and is passionate about expanding access to justice to the poor – especially women and girls. She has worked on grassroots justice projects with non-profits in Sierra Leone, Afghanistan, India, and Bangladesh. She’s fundraised for grassroots non-profits, worked for civil rights and legal aid organizations in the U.S. and represented immigrant survivors of domestic violence in Boston courts.

Brilliant perspective on the greatest problem with international development at the moment. The people with needs are not the boss, the donors are.

The question is, how many people and organisations working in the sector have the strength and presence of mind to take your first suggestion Akhila? To accept terms purely on their own terms (or more accurately, on the terms of the people we’re working with/for). My gut feel is that most organisations, particularly larger ones, are focussed on survival rather than on the need.

This is why I still think that only small NGOs can be responsible for identifying and addressing areas of unmet needs: http://www.whydev.org/how-only-small-ngos-can-address-unmet-needs/

You great list is similar to the list of criteria for accepting and rejecting aid that we developed in Palestine. This list: http://www.noralestermurad.com/2012/10/18/draft-criteria/ led to a Guardian article about “boycott thinking” — the only way that aid-dependent people can take back control over how resources are used on their behalf.

Such an important topic, Akhila, and you write about it so well.

I was particularly struck by your third point, as it’s something I’ve thought about as I work in Cambodia. Am I enabling the government to continue to ignore its role of providing social services because NGOs are? These are uncomfortable questions that need to be asked.

Allison, I think the answer to that is: it’s complicated. It depends on what the capacity of the government to provide those services are, whether there is a precedent or even an understanding of the need, and how the NGO plans on transitioning the provision of services across to government. I won’t speak for other sectors, but in the disability sector, I think provision of services is also the greatest tool to advocacy (and hence government provision of services that exist). Why? Because when you go into any poor community in Cambodia where services don’t exist and ask them – do you have any people with disabilities here, the answer is invariably no. But that’s because children with disabilities literally never leave the house. But, with the help of NGOs, they can get children out of their homes and into the communities, often side by side with non-disabled peers. This is how you get people to start caring about a population which is otherwise hidden. Get them side by side with non-disabled and all of a sudden the need for government provision of services becomes more apparent.

Pingback: 5 reasons why Save the Children Australia’s new ad is bad development | rachelkurzyp

Pingback: 5 reasons why Save the Children Australia’s new ad is bad development | whydev.org

Pingback: 5 reasons why effective marketing and good development work are inseparable | whydev.org

Pingback: 5 reasons why effective marketing and good development work are inseparable | rachelkurzyp

Its really very significant outlook.we too challenging deficiency in present system.and ivolved to menifest the parallel human society.i keenly devoted to the cause for equality In humanity.plz guide me for assistance.i am sure planed earth need desperately the innovative initiative Lovethouaim.