A Foreign Policy exclusive yesterday outlined the Trump administration’s budget proposal in March. Major implications to foreign aid include:

- slash aid to developing countries by over one-third

- folding USAID into the State Department

- 5% cut in funding for the State Department’s Bureau of Oceans and International Environmental and Scientific Affairs, from where the U.S. allocates $1 billion in commitments to the Green Climate Fund

- in general, rechanneling funding from development assistance into programs tied closely to national security objectives

Yes, these cuts will have major implications on U.S. aid funding. But will they have major implications for people’s lives in the Global South? It begs asking the question.

That’s why I’d like to see aid budget discussions framed with more nuance. In the effort to protect funding, often by sharing isolationist or nationalistic arguments like “aid stops epidemics from spreading to our people” or “aid helps curb terrorism,” we are deaf to a key reality: Aid needs reform.

I don’t have to relay the arguments for reform, do I? Ultimately, it’s a question of impact, but more so it’s a question of inequality. Aid is not neutral. And it is difficult to attribute societal changes to it. By and large, aid in all its forms often perpetuates ahistorical and apolitical approaches to development, rooted in a capitalist economic system. Aid flows are becoming less and less relevant within larger discussions of finance for development, which includes tax revenues and extractive industries. And despite this, the centrality and the hierarchy with which aid organizations portray themselves in the growth equation is staggering.

I doubt that many people in the Global South would argue for aid to be cut outright. Sadly, Foreign Policy did not report that they asked any people from the Global South in their story, just five white guys and a USAID spokesperson who is likely Clayton McCleskey, who, you may have guessed it, is a white guy.

I did not grow up in the Global South, but here are four reasons why I am Michael Stipe-ing this Foreign Policy headline and why I don’t think aid cuts are the end of the world:

More honesty

Aid has been tied to specific U.S. political or strategic objectives and interests since it began. The militarization of aid has always been present. Why cloak it in humanitarian terms? Under the immense shadow of “doing good,” much can be hidden.

Oh, that’s why.

Less modernization

We cannot deny that “traditional” societies being assisted to progress in the same manner as more “developed” countries remains as the enduring core of international aid. The limitations of neoliberal thinking about development from a Western-defined, economic growth-fueled perspective are hard to ignore. Our global corporate-driven food systems are broken. Inequality is soaring. And as the earth approaches its carrying capacity, our collective futures are threatened.

Maybe it’s time to stop exporting our “model” of development.

Less waste

Let’s not pretend. How much of aid money is actually getting to the ground anyway?

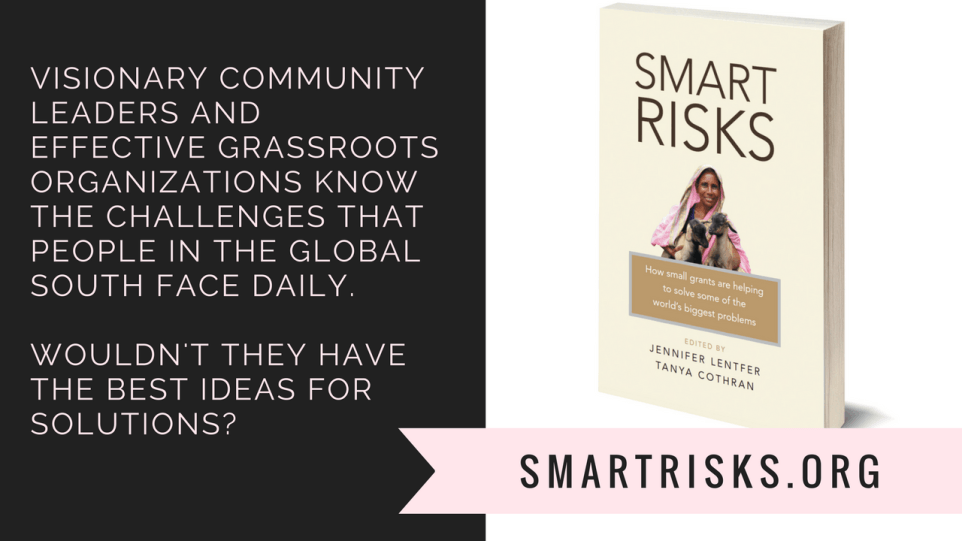

Less external “expertise,” more inclusion

Less infusion of external expertise might make more way for people with embedded, grounded knowledge. Maybe less “expertise” could make way for leaders, organizations, and movements, led by people of color, who are not in the business of aid to build careers and income, but are heading the call of needed social transformation to save their own communities. They have been doing less with more for ages – literally.

Maybe it is about context, not scale.

How can I talk about aid reform at a time like this? Do I want good people to lose their jobs? Of course not. But if we were attracted to and joined this sector because we wanted to help, then part of this work is about asking ourselves over and over and over again, what is most useful to people on the ground?

People have been getting on with their lives and making change in their own neighborhoods and nations, in spite of the U.S. aid sector’s efforts, for decades. That is why my work is no longer focused on global development, but rather global solidarity.

And that’s why, even with massive aid budget cuts looming, I feel fine.

***

***

Related Posts

Does aid need a 12-step program?

When an international NGO plans its obsolescence

A new kind of donor: 4 things they do differently

Getting money to the ground, directly

3 ideas for making locally-led aid responses a reality

Actually, it was my capacity that needed to be built

White supremacy, black liberation, and global development: The conversations we’re not having

Are the jobs of communicators changing in the development sector?

Yassssssssss this is everything.

Though still worried about all the shenanigans in the CSR space too, and just investments broadly. The amount of corporate funds messing around paving the way for extractive industries (in every sense of the term) is astounding.

But yes, I love this.

Fair points, but we should be terribly worried about these cuts being in the hands of Trump & Co, whose understanding of “nuance” appears to be non-existent.

Having now spent the better (or worse?) part of the past 17 years working for the UN, I’ll be at the front of the line to tell you what’s wrong with the UN and the first to point out some simple and incredibly cost-effective measures to be taken to make the organization less costly but more efficient AND effective while doing it. In fact, anyone worth their salt in this organization would be right beside me. This requires a scalpel, not a sledgehammer (a la “US cuts all funding to UNFPA”) approach.

Pingback: Trump and the Peace Corps | there is no utopia