A guest post by Chris Wardle in Nepal

“Is there any validity in local civil society’s perception that is taken more seriously by the donor community in Nepal, if it is represented by an expat?” an experienced fund-raiser from Europe asked me at a networking session on fundraising recently.

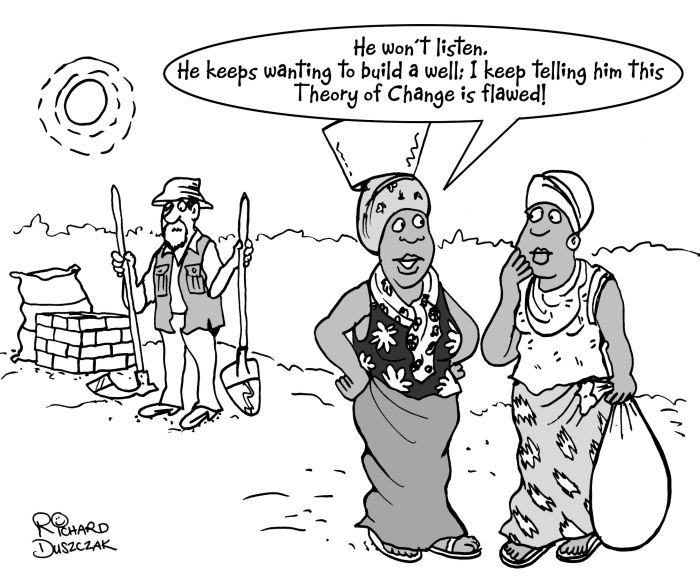

As an immigrant volunteer advisor, the term “expatriate” rubs me up the wrong way, as it pulls at too many strings of colonialism, paternalism, racism, exception and privilege – and not just in this country.

On the need for expatriate representation, my interlocutor and I agreed that neither of us subscribe to the “white saviour” mentality in fund-raising, nor in development work at large, preferring to support the nurturing of donor relationships by promoting Nepali staff, partners, and the people we serve. Enthusiastic as I am, it is first-hand experience which brings much greater knowledge and passion about the results.

Consequently, much of my earlier work has focused on team-building and coaching both senior and middle management (of civil society organizations) to be able to confidently engage with donors as potential partners in development. Adopting this approach, I have never felt that my presence was more preferred or important, as I was focused on uncovering the synergies between our our strategic direction and that of our potential donors. I only really feel that I have achieved my goal when my presence is in fact redundant. This, in part, has relied on:

- the comfort level of people to be ready to step up and take the lead role;

- clarity of organisational strategic direction and its links with the aims of the donor in question; and

- embracing a development partnership approach, rather than that of a servile, cap-in-hand beggar.

That said, regrettably I have seen the donor condescension implicit in the question, exhibited by small number of folk here in Nepal and elsewhere. Sadly, it has been from people falling into two broad categories:

- Desk-bound donor staff, both from the country and immigrant, who have not had – or perhaps taken – the opportunity to visit the programmes that their funding supports; and

- CSO staff letting their ego, caste-discrimination, or petty power-politics get in the way of results.

In looking for a way through such challenges, for the former my approach has been to encourage donor staff to participate in review meetings held in the same city as their office. A simple act of this nature at least opens up the chance to meet people who are at the forefront of programme delivery and paves the way for helping extract them from their desks and sample “the real world” of development assistance. This type of “donor engagement” also helps CSOs avoid being our own worst enemy, by not confusing the common humanity of people with the money that we have extracted – or hope to extract – from them.

Sadly, the second scenario is contrary to my usually joyful, day-to-day experience of working with and being amongst Nepali people. While discrimination based on caste is illegal under the Constitution, its cultural roots run deep. That, combined with the fragile egos of those holding onto the “power” of the purse strings, has revealed itself to me in entrenched, ugly, master-servant relationships and an unwillingness to embrace the true spirit of partnership.

Apart from calling-out such rude, petty, discriminatory behaviour, I can offer no immediate solutions.

However, I feel strongly that if we are unable to counter this nonsense and advocate for civil society organisations to be regarded as equal partners in development, it severely compromises our ability to be effective advocates for marginalised people.

In closing, I hope, dear readers, that you may share in the comments below, your experience and the solutions which have helped you to avoid a reliance on expats, white saviours, and local masters.

***

Permaculture student, dreamer, poet and development worker Chris Wardle is half-way through a one-year volunteering placement in Kathmandu, Nepal. He is passionate about thinking critically about impact with people and ensuring that programme design and fund-raising truly reflect the needs of the people.

***

Related Posts

When an international NGO plans its obsolescence

How would you measure the strength of a partnership?

Knowing when (and why) to stop and listen

Are NGOs missing the impact forest?

Chris Ji,

This is a brilliant article and I think describes many of the challenges of development in Nepal quite well.

I think, based on my own experience , some of which we have shared, is that there are a number of disfunctuonal systems at work that contribute to a disfunctional aid and development sector in Nepal. I think you are right in your comments about a kind of detached psychology and practice in development which is at odds with sound methodology as well as a mentality around the ‘short term’ and this pervasive idea that any money, on any terms is good.

I keep returning to a Herman Melville quote “must money be the measure of everything we do?”. I acknowledge money is important but I think it is equally important, as you rightly point out, feeling respected and valued as a true partner. I have seen first hand the shift from being bullied and berated to being appreciated and valued and I know which one I would prefer. I would take a partner who respects me but offers less cash flow over one that is high paying but treats me like garbage any day.

In regards to the expat and white saviour thing, this is very troubling and very difficult to unravel. I have found being “the foreigner” has unlocked and opened doors that may have been closed to my local colleagues. We have both faced I think, duplicitous dealings in ourselves being treated differently to our local counterparts.

I think some of this stems from how foreign aid workers see themselves. It is not universal but I continue to detect an ongoing mentality from many others in the sector that they are right, their education etc is superior and their way/ “our way” is better. While I have concerns and some complaints about some of the operations of my own host organisation and other organisations I work with in Nepal, I do not believe at any time that these are due to some failing, inferiority or incompetence on their part.

Further, much of what I was told prior to and at the time of arrival about the competence of Nepalis and their organisations was broadly negative and has turned out to be untrue and heavily exaggerated. I find that these opinions and perceptions came from others involved in development in Nepal very troubling.

I worked for a time in Mission Australia and I remember the participants of the project telling me they had seen many facilitators who didn’t truly care about them, it was more to build that facilitators profile. I told them “I will not build my career on you namesake and at your expense”. I think we need to do away with the othering in development. To stop seeing people, their lives, their communities as resume building or fund winning resources. You speak of the shared humanity, I think we need to seek that out and embrace it. Walk a mile in people’s shoes, try to think how you would feel if some foreigner came to your home, your place of work and behaved in the way many do here. Offered you advice, acted like an expert on how you should do your job.

In my own practice something I am going to do more of is speak Nepali at work. Ma thorai Nepali bhaashaa bolna sukchu, Tara dherai bhujchu. I speak some Nepali and understand more. I sit on this ability and do little with it, I am committing to using it more actively, to let people know I can understand and communicate with them, to be less accepting and passive of being translated and translated to. I envision and hope this enhances my effectiveness and relationships in working with Nepalis.

In solidarity as always,

Brent

Here is someone describing her experience of her “presence more preferred or important” in Uganda: http://www.whiteheadcommunications.com/blog/white-privilege-as-ive-lived-it-in-uganda