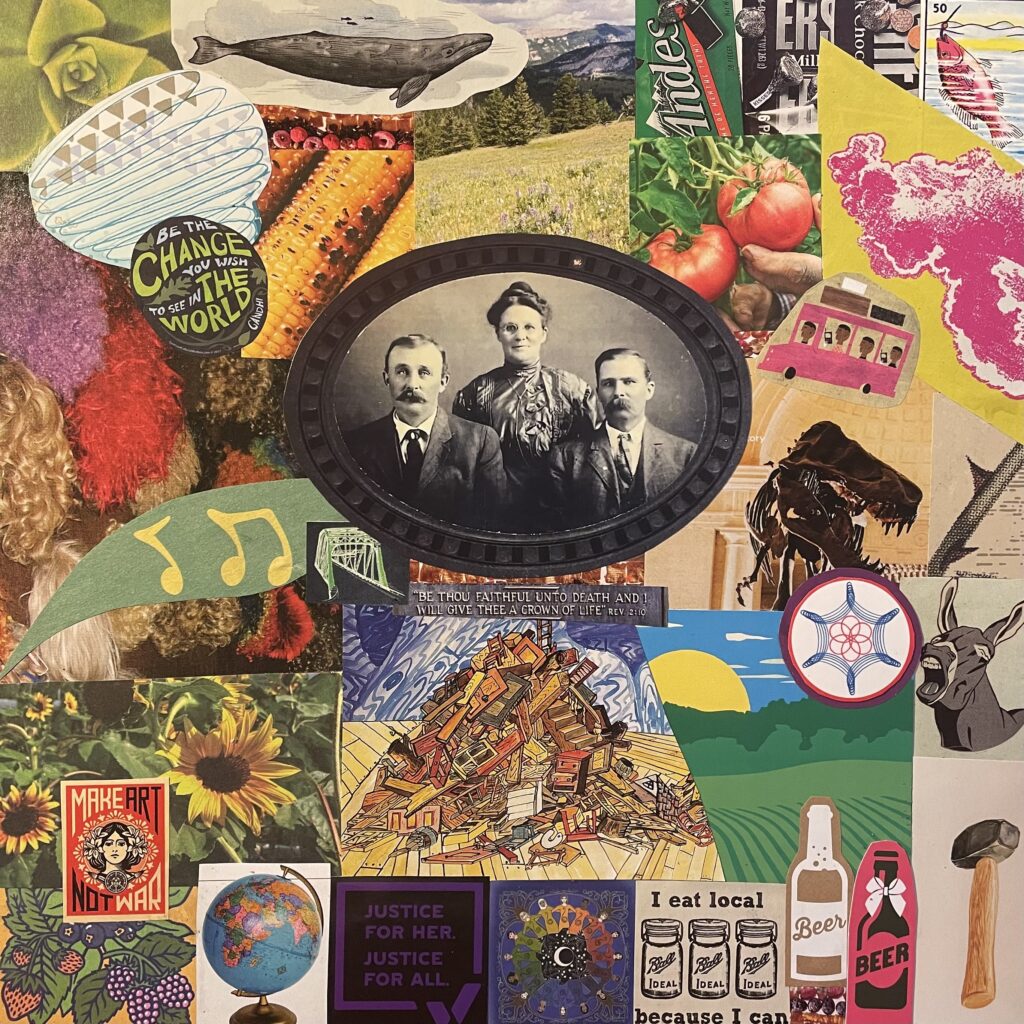

My collage above is entitled, “What is tender III” (2021). On the left of the black and white photo is my great great grandfather John Henry Hulse (b. 1872 d. 1947), with his two siblings, his older sister Maggie Hulse Casper Gerdes Wilhelms (yes, she had three husbands!)(b. 1869 d. 1946) and his younger brother, Hei Henry Hulse (b. 1875 d. 1937). They were “first generation” Americans. Their parents were born in Hanover, Lower Saxony (Neddersassen), of what is now Germany.

My grandmother tells happy stories of going to her Grandpa John’s house after school everyday, since he lived across the road from the schoolhouse. He would share a treat and she would ride his pony and feed his pigeons up in the hay mound. My grandmother’s sister tells stories of Grandpa John’s nine children running into the cornfield for safety when he was in his drunken tirades.

Every family contains complex and painful and nuanced stories. I have always been someone who noticed and remembered what stories were told in my family, which ones were not, and by whom. From a young age, my spirit wanted to understand the fragmentation caused by settler colonialism – showing up as abuse, addiction, domination and control in our families – even if I didn’t yet have words for it.

As my political education about the oppressive systems that I’ve benefited from continued, it necessitated that I learn more about my own family history, and our sources of wealth that have enabled my study and work and life. It’s not an easy reflection. There’s pain from patriarchy, white supremacy, and capitalism that all of us need to process and understand, in order to re-establish those connections that are severed.

These are really big systems that sever and fragment our families. They sever us from our bodies. They sever connections across language, creed, tradition, etc. So the work of reconnection is really about understanding our own pain, first, so that we can turn back to “we.”

In the ‘do-gooder’ paradigms we live in, we’re attempting to support other people to overcome things. And if I’ve said it once, I’ve said it a thousand times: If someone is comfortable in their privilege, and not really interrogating their own sources of struggle, how in the hell can a person show up for others who are part of the peoples’ struggle?!

“Go get your people,” i.e. go organize other white people to learn what we’ve taught you, is a mandate given to me many times over the years. For a long time, I didn’t quite know what people of color meant when they said this to me. I had to develop my own hard skills and emotional resiliency to understand how I could interrupt racist systems and behaviors and build new ways of working in the international aid and philanthropy sector.

The day after the 2016 U.S. presidential election, my then boss Rajasvini Bhansali called me. She said,

“I’ve been listening and too many white people tell me, ‘I don’t know how to talk to my own family. It’s too triggering.’

“Look at that cumulatively,” she said. “It is that deep, intimate pain that we need tools around.”

Cumulatively, it had resulted in the election of Trxmp the day prior, and today it continues to result in rising white Christian nationalism in this falling empire. It was a clarion call.

It took time to understand that what Vini had offered to me in that moment was an invitation to practice a multidimensional love, a love that holds the both-and’s of our humanity in recognition of the relationality to all Life. A love that contains both my grandma’s and her sister’s stories about the same man, and the opportunity to end cycles of generational violence by doing the deep, intimate, courageous work of relating to my own people.

Learning to extend ourselves and our solidarity to people with such vastly different lived experiences can be such a healing and fortifying aspect of our collective liberation. Building our willingness and growing our ability to sit with and claim the painful questions that this brings up is crucial.

But in my experience, responding to Vini’s invitation and turning my attention to include people with similar early lived experiences to my own have been some of the more challenging aspects of my journey.

To understand how we build a system that gives everyone what they need includes me and people like me “giving up” some of our power and resources.

It’s a hidden hurdle that we have to name and wrestle with. These have been some of the most terrifying risks in my anti-racism work, to break the “silence code” of privilege and comfort among my peers, that is, family and friends with similar backgrounds and access to resources as me.

In this year of living back in my home state of Nebraska, the question has become: How do I extend my love to the people who still represent from where I’ve come – that is, the previous versions of myself?

Decolonization is not about rejecting history. It’s about recognizing, interrogating, and challenging the forces/impact of domination, oppression, and external control in our lives (bodies, families, organizations, institutions, systems) that remain today. It’s about recognizing how those forces separated humans (the colonized AND the colonizers) from our intrinsic worth, our true natures, and from each other. It’s about recommitting to what is sacred and eternal – love, care, togetherness, Spirit, and Mother Earth who sustains us all.

What I want to uplift as we wade through what’s tender and tricky and hard is that there is something on the other side, and that is more connection, joy…glory! That is what many of us signed up for when we entered the social good sector. We signed up to make the world better. We didn’t know we were going to have to interrogate our own families, and we didn’t know we’re going to have to reform our own organizations. My goodness, that’s so much! And it’s okay. Loving – or shaping how it feels as we’re doing the work together – is actually the work. Keep going.

“Love is space; it is developing our own capacity for spaciousness within ourselves to allow others to be as they are… To come from a place of love is to be in acceptance of what is, even in the face of moving it toward something that is more whole, more just, more spacious for all of us.” ~Reverend angel Kyoto williams

***

Related Posts

Leading From Love: The attentiveness that brought accountability

Grandpa, the Marshall Plan, and me

Wrestling with my white fragility