Aidspeak called for three changes to make aid better by August 1st. Oops – instead they’re getting one by August 3rd.

***

Give every aid worker (local and international, cleaner to country director) a social change investment fund of US$1,000, over which they have total personal discretion.

Task each of us to find an “under-the-radar” grassroots organization, leader, or initiative worthy of support. The only stipulation is that as fund managers we must find a group that has been in existence for at least three years and has never received international assistance. (With estimates of grassroots organizations around the world at four million, this will not be as hard as some may think it sounds.) Only one-page proposals and reports allowed.

Aid workers spend plenty of our time in budgets and logframes. What will happen if we have total freedom to break the rules…take a risk!?! During the year, the fund managers will also be tasked to just have fun! We must find a person, an organization, or an idea that inspires us. We can learn more about a topic of interest. Our mandate will be to tap into the enthusiasm that drew us into this work in the first place.

At the end of one year, the fund managers in every organization get together and share what we’ve learned through facilitated and documented reflection exercises. We distill good practices and actionable insights. We will let the truth hang out. We will admit that some investments didn’t go as planned.

We will let that be okay.

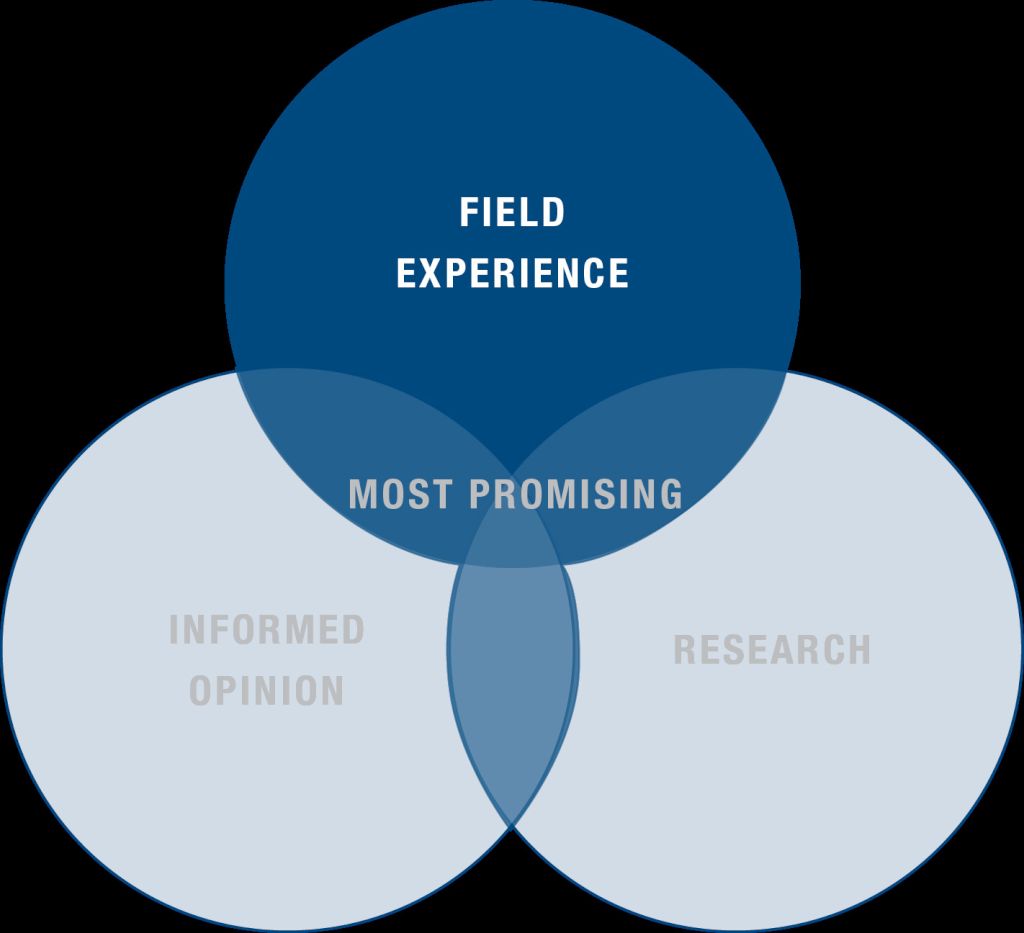

If we are serious about “flipping the aid system” to put more local and national actors in the driver’s seat of development, we have to let go and learn in myriad different ways. These social change investment funds could help us release the “pressure” of bringing about large-scale impact in order to more deeply understand the local processes that bring about change. If we’re forced to think micro, we may actually build a more inclusive discourse on aid that changes our understanding of what we value (local ownership) and what we measure (social change).

When I started how-matters.org two years ago, I reached out to about 150 colleagues and friends around the world and asked them to respond to:

If you personally could do one thing to change “the system” of foreign aid and development assistance, what would you do? (You can see their responses here, here, and here.)

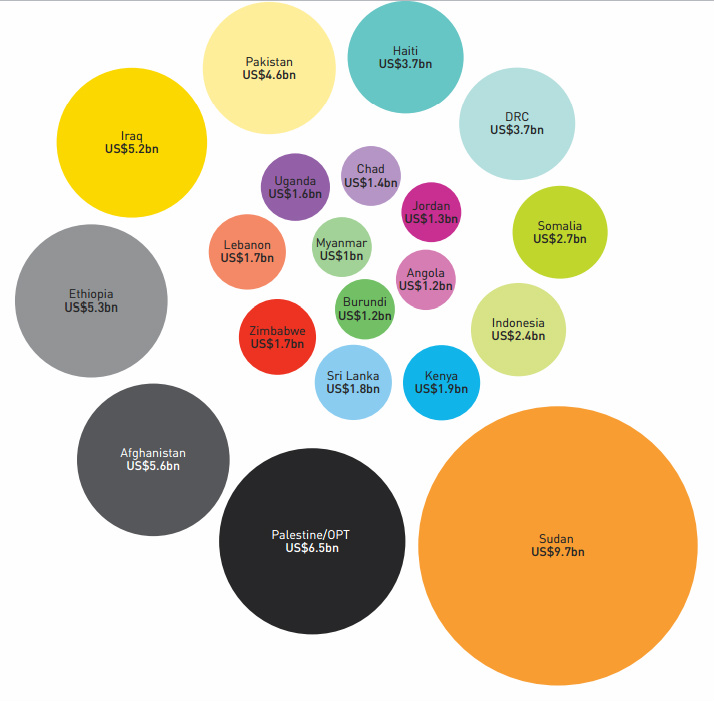

I asked because the estimated 595,000 aid workers around the world (see “The State of the Humanitarian System” from ALNAP, 2010) are rarely called to examine the bureaucratic rigidities that govern their day-to-day work and that deflate and/or marginalize local activists.

With just $59,500,000, one in ten of these aid workers could try out the investment fund and learn how to change the corporate culture of aid agencies that no longer meets the demands of a rapidly changing world.

Consider that this amount is just 0.002% of what rich countries delivered in aid to poor countries between 1960 and 2008, which the World Bank reports as $3.2 trillion. Consider each layer of the aid system taking its cut in those decades before funds ever reached the ground. Just think about that.

And if $1,000 is squandered or “goes missing” here and there, well, let’s just see that as the cost of doing business—much in the same way hi-lux trucks and school fees for international staff’s children are seen as the cost of doing business now.

Is sixty million dollars too much for a year-long “experiment” with so few guidelines and so little “accountability”?

If the well-intentioned, smart people who are ill-equipped and not incentivized to challenge the aid industry’s linear and hierarchical structures can be enabled to change their roles from purveyors of knowledge to investors in potential, this is a relatively minor gamble.

If we have an opportunity to create more trust, equity and mutual accountability with those we serve through investment funds and see for ourselves how a diversity of approaches and actors unleashes social change, then the system-wide reforms needed become more feasible.

So let me have it. Tell me why this wouldn’t work.

But know you may run the risk of being called a big ole’ fuddy duddy.

***

Related Posts

Bottlenecks and Dripfeeds: How much has changed?

A new kind of aid donor: Four things they do differently

What a great idea! In fact it has already been tested for decades and is in my opinion the most effective grantmaking method:

Welcome to Peace Corps Small Project Assistance

http://idea.usaid.gov/ls/small-project-assistance-program

With an even better twist: Chosen projects must be met by a 50-50 effort match from the community served.

The Peace Corps SPA grant program is a great idea in theory, but in my experience with it, the proposal and reporting framework are too rigid to allow for the kind of play and experimentation that Jennifer describes here. SPA is not about investing in people or ideas per se, but traditional projects. It’s not really designed to challenge the paradigm as Jennifer describes.

Excellent suggestion. One thing to think about, though, and this does not take away your suggestion’s excellence, is what comes after that $1,000? I’ve seen lots of stalled small projects around the place which were hamstrung by their inability to take the next step. Constraints are not just finding more money – though that is certainly important – but getting the necessary advice and support to grow. Such advice and support does not come cheap and could be a major challenge to provide.

This is a really unique idea, and I think it would have great potential! As someone who is only just starting to break into the aid field, I would really love to see this implemented during my time in this career.

I have a few questions and comments (not to diminish your idea, which is extremely well-thought out). Firstly, perhaps this is an obvious answer that I am overlooking since I do not yet work in the field, but who provides the 1,000 USD? Does it come from the aid budgets from donor governments or from the aid organizations themselves?

Secondly, I agree with MJ on needing to consider what happens after the $1,000 is depleted. I think if we wish to change the aid system, then we need to start thinking more seriously on the issue of sustainability. As you rightly stated, finding a project/person/idea to invest the $1,000 in is the easy part, but once the $1,000 is used, the project/idea might still need a continued flow of resources. And if the assistance/partnership ends once that $1,000 is gone, then the project/idea might not continue.

However, I think that having a limited timeframe to invest in these ideas/people/projects is necessary because the last thing the aid world needs is more endless pits consuming funds. And also, having a limited timeframe might urge the investors to make sure that their “investments” are truly effective, which would then allow the best “investments” to survive. This somewhat sounds like survival of the fittest in micro-aid projects.

All in all, I think this is a wonderful idea, especially since many aid workers don’t have the chance to break from the rigidity of their organization and use their creativity. Another reason I see great value in this is because it gives the opportunity to give people/projects that are not in the top-10 or top-20 aid recipient countries, which might well encourage further development in the ‘neglected’ countries.

Great thinking and wonderful post!

Cheers,

Karen

Thanks for all of your comments. By and large, I want aid workers to have a different experience – not one of acting as technical experts or administrators of funds, but as investors in local potential. It requires a different set of skills, but more importantly a different mindset.

I think the issue of “what happens after the funds are gone?” is not unique to small grants. What’s different from a larger initiative is that we the aid workers actually feel it and will have to look the people in the eye that will struggle to continue after the $1,000 is gone. By now, people in the developing world are very used to the floods and droughts of aid funds. The most effective community groups I know have contingency plans and ongoing local resource mobilization efforts to make up for this.

Oops, I just gave away one of the criteria I would use to determine where my $1,000 would be going. See how this starts to work…

I think the 50-50 shared community effort of the SPA grant is what makes it great. The money doesn’t drop to zero at the end of the grant, because half the money / effort / resources should have come from the community itself. It is AID TO, not a replacement for the community’s own capacity. Peace Corps has definitely gotten more bureaucratic, but the concept here is still good. Last time I saw a SPA grant form is was only one page of documentation for up to $500. That doesn’t sound bad to me.

Pingback: AidSpeak

I very much agree with you on this! You have put everything I champion for into perspective. Let the aid agencies read this! With these little efforts, we can change the attitude of aid agencies. I have a big issue with aid organisations as its proving very difficult for grassroots organisations around the world, particularly in developing countries to access donor fund particularly those that lack the skills and technical expertise to break the rigidity of donor aid requirements to write ‘good proposals’ that the aid agencies are looking for! I am therefore campaigning for favourable donor-receipient policies. Check this out: http://www.reworkdevelopment.wordpress.com . Thank you so much for this!

This is very unique and good idea.Good especially considering that there are now a lot of good initiatives by local NGOs who are failing to get sme funding because they are not 3 years old or because they have not been funded by someone else.The idea is also good in that it gives the NGOs an urge to perform to prove their trust and worthy.