I’ve been invited to speak at my alma matter and so I’ve been eagerly reading fellow bloggers’ recent advice for students and aid career seekers. See Tales from the Hood’s posts on Motivation and Sacrifice, one from Satori Worldwide on whydev.org, one from La Vidaid Loca, and another from The Principled Agent. Here’s a few of my thoughts on the subject (en hommage a Sy Safransky) to add to the mix.

***

When I came out of grad school, I was programmed to think macro, think sustainability, to think that development economists had a clue (do they?), to think, think, think. In essence, nothing in my training prepared me for what I would feel as an aid worker.

***

The mantra “what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger” comes to mind. And the trauma, the vicarious trauma, the loss, and the isolation that aid workers can face indeed may make you stronger. Unfortunately, what makes you stronger might also make you less sensitive, hardened, more disconnected, less caring. Thus with all of our conditioned tendencies to avoid suffering, self-critique and self-compassion must be your constant companions.

The mantra “what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger” comes to mind. And the trauma, the vicarious trauma, the loss, and the isolation that aid workers can face indeed may make you stronger. Unfortunately, what makes you stronger might also make you less sensitive, hardened, more disconnected, less caring. Thus with all of our conditioned tendencies to avoid suffering, self-critique and self-compassion must be your constant companions.

***

The over-intellectualization of professional aid work is staggering to me at times. Yet I still often find myself wondering, in relationship to various projects, “What were they thinking?”

***

No matter how self-aware you come into this work, most people, especially in the beginning, will be operating from a worldview in which change in poor people’s lives is possible with our help and that it was something that can be “managed.”

In my mind, the jury is still out on this.

***

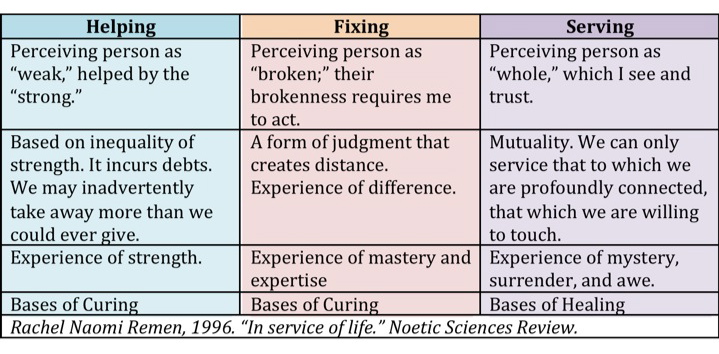

When I first saw this graph, I thought, “Gee, this would have been helpful” as I worked to discern my ‘calling’ from what the aid industry was requiring of me, i.e. think-think-manage-manage, and what was actually happening on the ground. The difference between helping, fixing and serving presented below is intended for health care providers (click here for table if on main page), but I think it has real relevance for aid workers and do-gooders alike:

***

A quote I always keep nearby:

“If you believe if you’re going to…change the world, you’re going to end up either a pessimist or a cynic. But if you understand your limited power and define yourself by your ability to resist injustice, rather than by what you accomplish, then I think reality is much easier to bear.” ~Chris Hedges

***

Even when real changes in people’s life conditions are not imminently possible, our role can be to enable hope in the face of adversity.

***

What is required of aid workers to serve rather than help, is illustrated further by a concept my friend Silvia brought to my attention, that of “cultural humility.” She works in hospice in California, working with healthcare professionals to offer more appropriate and compassionate care to the Latino community. In healthcare settings, cultural humility involves active engagement in self-reflection, bringing power imbalances into check, relinquishment of the role of expert, becoming the student, and seeing a patient’s potential to be a full and capable partner in their recovery.

The most effective and inspiring development practitioners I’ve ever worked with embody cultural humility.

***

Do you have the courage to battle the modernist viewpoints, privilege and racism at the roots of international aid, as well as to question your own personal prejudices, stereotypes, and agendas? Be prepared to go deeper to examine your own beliefs, values, assumptions, and biases. Karen Armstrong describes the “hard work of compassion” as constantly “dethroning” yourself to challenge your own worldview.

***

Maybe the title of this talk should be “What I had to un-learn from grad school.”

***

I do think there is room for aid workers and do-gooders to redefine our role as translators, between what people on the ground really need and that of the demands of donors. Not as providers of what people need. Not as enforcers of policy, or rules, or regulations. Not as helpers or saviors or martyrs.

***

Results, results, results. Yes, they are important. Results are not possible, however, without tending to “the process.”

You will have many bosses who do not understand this.

***

You will have to fight hard to not let the overly technocratic, abstractionist tendencies of aid work pull you under.

You will have to fight against “charitable” urges towards impoverished and marginalized people you encounter, which can ultimately debase their dignity.

You will have to fight to experience the full range of our human condition.

***

Anyone can identify what’s wrong. It will take much more skill and strength to wake up everyday and help identify what’s right, what’s possible, and where incremental changes can occur.

***

…Just a few of the things I wish I had known. What about you?

***

Related Posts

Beautifully expressed! I really liked the bit about “cultural humility”…

I found your comment about aid workers as “translators” intriguing. Can you elaborate on this idea?

I agree with Rachel. I’d be interested to hear and think more about this concept.

@Rachael & @Tanya I’ve been thinking about this concept since watching founder of Global Voices, Ethan Zuckerman’s TED talk: http://www.ted.com/talks/ethan_zuckerman.html

I think that along with the rest of the world, aid is in a period of transformation. I hope that aid workers will no longer be called upon to serve as “experts.” Rather, we will help identify what is in communities that is authentic and that has potential, accompanied by a deep respect for local and indigenous initiatives. I believe communicating this “up the chain” in the system, in order to make aid more responsive and relevant, will be a key role of development practitioners in the future.

I think you’re getting at some key points. Two thoughts, neither of which contradict what you’re saying:

1) It’s true – grad school didn’t teach us how to “feel.” As important, it didn’t teach us what we would actually spend our days *doing.* Studying, say, “sustainability” is important. And who in their right mind would argue against sustainability? But on your first day on the job, sitting down at your desk, booting up your computer, all fired up to “ensure sustainability”… what do you actually do? No one told us this. The gap between theory and practice is huge. This is my biggest issue international development degree programs.

2. I have said many times that humanitarian work is characterized, more than anything else, by paradox, dilemma, and irony. Love the development economists as I do, I have to say: this is not science; data is frequently not what it seems; local context is a hugely unappreciated mess of variables. The laws of untended consequence reign supreme. Things very often do not work out as planned. After ignorance of actual humanitarian practice (point 1), the unpreparedness to cope with the paradox, dilemma and irony is probably the most important single challenge of the fresh-faced grads that I see coming into the field/industry.

Steve on the Peace and Collaborative Development Network shares: “We have to start somewhere, usually with paradigms taught in institutions that we must re-forge into our own usable tools honed and tempered though trial, tribulation and error, until dulled and twisted by difficult challenges not overcome, we come to the ego deflating realization ‘I do not know enough’; only then can we identify what it is that we wished we had known, only to learn we already knew through seemingly inconsequential moments in the past; until one day we understand ‘I can never know enough’ and we cry, soothed by those we sought to teach ‘it is as it is’ they say, ‘what can we do but keep on trying.’ And so we keep on learning and applying through experience and perseverance what we had wished we had known, comforted by the knowledge that if we had waited until we knew what we needed to know, we would never have made it to the bellows; so undeterred by the realities that what we know and what we accomplish will never be enough, we keep on trying.”

And Christian on LinkedIn shares: “If I had only known (or better known) that politics and selfishness is everywhere, then I would be more prepared to deal with the problems generated by all those who are in the ‘do-gooder endeavour’ just for their own benefit. This is the main constraint and challenge to face. The good thing is that there is enough good people. We just need to be aware about those who are making bad noice and bad troubles. The bad thing is that normally,. those with the will and dispossition to be ‘on top’, are ruled by their ego and their selfish interests. Transparency of information plus multilayer and multidirectional networking is a tool to make evident with whom one should be involved and from whom one should be alert…. this is something I would like to better know before geting involved in development.”

Jeniifer your words made me think, the work I do. I have felt disappointing in many times, seeing the people wha are there to do things they simply ignore the work making people suffer. Its a kind of lack of humanity. I think the basics of huamn is lacking

Great post. I too enjoyed your picking up on Cultural humility. Interesting how marketing and usability perspectives both pointed me in that direction. So the ‘demand driven’ approach was the only one that made sense.

***

And seeing so many others talk at people about solutions. Listening and learning the father of solutions that work for the customers

***

Have you been reading Kurt Vonnegut lately? I love his stuff!

Thank you for your thoughts. I am about to graduate with an MPP and would like to improve policy and conditions for undocumented migrants and assylum seekers. Your article really helps ground my thoughts as I seek positions in this field.

In my work in Restorative Justice with youth and in my hospice work Serving is the paradigm. Hospice focuses on Healing, which comes from the same root as the word Whole and healing can and does happen without curing or fixing. As Rachel Remen says,Service is the basis for healing and it embraces mystery and awe, the capacity to hear and see a person or community’s wholeness and their wisdom, strength, capacities and resiliency and whenever we can, reflecting that back to them.

Council process,Talking Circle or Restorative Justice practices and processes are GREAT ‘tools” for Aid Workers…because these practices all rely on respect and deep listening.

Translating is always the great challenge in the work I have done. Process is by nature experiential and more challenging to translate into donor or policy language. Translating well depends on entering the “body” of what is being said and translators are of course skilled in more than one language.

And the best translators have focused on developing great “listening skills”. They not only read the words, they get the nuances and the feelings and context behind the words..so they can express the heart of what is being said to the people who need to hear it (donors in your piece) in the language that they best understand.

Deep listening makes that possible. It requires authentic interest,openness to new understandings and an awareness that “The Map” no matter how sophisticated it is, or how much data went into making it – IS NOT The Landscape.

Landscapes are fluid, living, they change. And maps get re-drawn! When we keep that in mind we can see the Landscape we are in just as it is, seperate from the map. That kind of vision illuminates the landscape we’re in, rather than trying to fit the landscape to the map we were given.

I have a degree, but I am not an academic…or a researcher…(though I learn from both) but i know in my bones that there is spaciousness created when we listen deeply and in that spaciousness wisdom and creativity and true understanding can arise.

Thanks for the inspiration and the conversation.

Celebrate diversity in all its forms, for through diversity comes strength and resilience. Lessons in all forms go both ways, sometimes learned but often not. Cultural awareness is part of the translation job that you, perhaps, take back to the donors…?

I agree that graduate school does little in the way of preparing us for the complexities and complications we will face in the field. It also generates its own breed of cynicism that the “too big to fail” organizations and people involved for the wrong reasons will always exist, and always find some way to override the work of those that have this kind of handle on their role in the “development” world. This cynicism grows deeper as it seems the dialogue in so many courses does focus on this macro sense of bringing people out of poverty and developing whole countries and not this concept that as a person or a group, focusing in an individual, a household, a small community, it the real way to see feasible results, understand what people really need, and not feel completely defeated before the log frame is even sent to the manager at the desk in D.C.

These are certainly important things to think about, and until course work in graduate school trends toward the feeling side of aid workers and fosters some sense of optimism on smaller scale development, it seems us students just have to slug it out together and open to dialogue amongst ourselves and turn to these blogs that provide a wealth of information we can’t find in the classroom.

Great blog! When we begin to understand that people are at the centre, and are the rationale for all our “development” efforts, then maybe we will learn to listen twice as much as we talk, and serve more than we help.

This post also appeared on:

whydev.org – http://www.whydev.org/if-i-had-only-known…/

& Mindfulness for NGOs – http://mindfulnessforngos.org/2011/05/25/i-want-to-be-an-aid-worker/

Pingback: The Girl Effect and dignity | Gypsy Girls Guide

I think most of what you say here, especially the graph and quote by Chris Hedges, must apply to donors as well as aid workers. This conversation (but not your speech) could also be expanded by including race, power and privilege. Where donors stand on these skews so much of their work towards helping and fixing instead of serving.

Great thoughts. I like the incremental idea especially because of its implied link to learning the way there… Which links to the problems with results orientation and our need to being open to possibilities that emerge from people on the ground being supported to try/fail/learn/try again and find their strength and way forward… Their stronger processes (including their developing organisation are key results)… To be honest, for me, the service and humility thing may be ok as a phase but not as a philosophy or state. I would like a world where no one has to be a humble servant to anyone else. Ultimately we stand or fall together as equal beings trying to save a dying planet and create a beautiful world we can all live in.