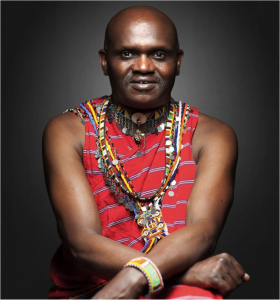

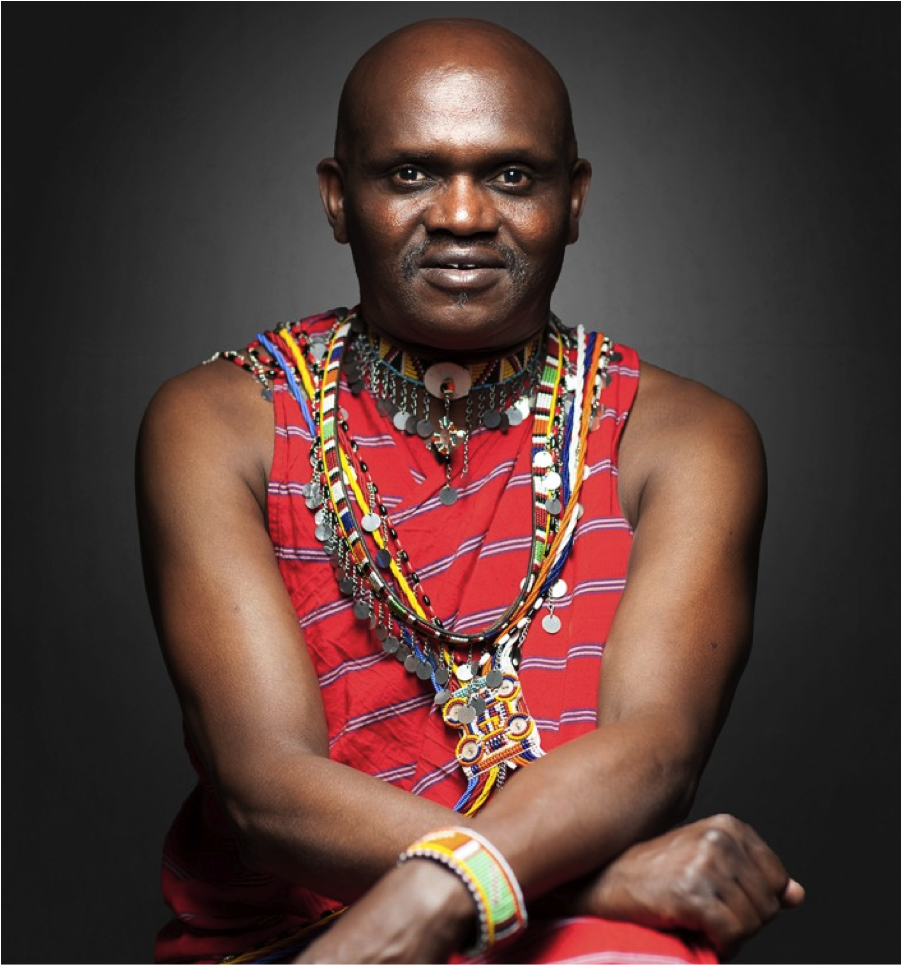

Koissaba Ben R. Ole is a PhD candidate and research assistant at Clemson University.

I was employed by World Vision as a community motivator in one of their first Area Development Programs (ADPs) in Kenya in 1987. During these many years of getting exposed to both theoretical and practitioner perspectives of community development, I have, more often than not, found myself wondering about the real drivers for community development. Is community development a product of theoretical frameworks? Or is it a practice that is driven by peoples’ desires to change and adapt to the demands for survival within their specific geographical, social-cultural and political environments?

Showing respect for development as an inborn process

Through my work with communities, one key lesson that kept emerging over time for me is that no one can ever develop another person. The potential and ability to develop already lies within individuals – in their aspirations for their lives. The role that NGOs and global development forces play is to provide information on that will help others make informed choices on how they will achieve development within their context. When global and local players think that their interventions can develop other people, they forget that the people they normally referred to as the “targets” for their development projects are independent individuals who think and believe that they already have the capacity to develop.

This is why the current and past development approaches in the community development arena, where the so-called experts from the “developed” world spend time and other resources to help the underdeveloped world, is in my perspective a displaced and outdated process. There is no need for anyone to be convinced that their way of life is inferior and needs to change.

This is why the current and past development approaches in the community development arena, where the so-called experts from the “developed” world spend time and other resources to help the underdeveloped world, is in my perspective a displaced and outdated process. There is no need for anyone to be convinced that their way of life is inferior and needs to change.

The description, or the construct, of change in community development is also problematic. In common practice, change is the process of transforming a situation, acting, projected behavior, perception and norms. But who drives the change? Change from what to what? Why and how? If the question of change does not come from within, the need to change is imposed. One element often missing in the community development process is the ability to provide answers as to what change and why the change. Naturally human beings change in response to their environments, and the best change comes from the community when they can collectively make decisions as to what needs to change in their lives and why the change is needed.

Where theory and practice can converge

Three years ago, when I started learning development theories, I discovered how hard it is to theorize about community development. I had worked for over twenty years “doing” community development by responding instantly to the actual needs, desires, and aspirations of both urban and rural communities in Africa. Before I started studying, I didn’t think much about the tension between delivering community development initiatives and the processes and theories behind why deficiencies occur and the relationships between problems on the ground and the interventions that are put in place to either forestall or mitigate their impacts.

As a practitioner I took for granted the importance of theories and empirical research. Instead, I specialized in participatory action research that not only provided hands-on experiential training and practical answers to what community needs were, but ensured a sense of ownership in the whole process. My concerns were about limited funds and what could be better spent on urgently-needed programs, rather than engaging in more academic and theoretical research or project overhead costs which included salaries for personnel who were highly-schooled. (Note the difference between highly-educated.)

While researchers grapple with theories and frameworks for certain behavior patterns and possible causes of community challenges, development practitioners are right at the core of it all. They interact with the communities every day at every level; some even suffer the same predicaments that the communities they serve suffer.

By helping to identify patterns in practitioners’ work, these patterns can be theorized, tested, and used as models for community development with the assistance of researchers. Learning about the strengths, weaknesses, and tensions within community development practice and theoretical models, helps both practitioners and researchers understand better why they each of them have often excluded each other from their work and how to reverse this.

It is important to note that in the field of community development, it is not the position or title, neither the model and make of the car that the aid workers or researchers drive that matters.

It is a big heart, a good brain, hawk eyes, and good ears that are willing to listen. It is humility and the patience to walk the path of community development at the pace of the community.

This should be the starting point for any theory in community development: people’s emotions, motivations, interactions between themselves and their environments, their interpretation of challenges, and willingness, readiness, and know-how to change what they want to change.

***

Koissaba Ben R. Ole is the author of Local Advocacy to National Activism: Maa Civil Society Forum, Kenya. He is currently completing his PhD in International Community Development at Clemson and has his MA in Social Entrepreneurship from Northwest University. He is an outspoken advocate for the land rights of the Maasai people.

Since the late 1980s, he has worked as staff and as a consultant with various local and international NGOs, government agencies, and think tanks in Kenya, including World Vision, Premese Africa Development Institute, the Kenya National Poverty Eradication Commission, the Indigenous Concerns Resource Center, and Keekonyokie Oike Suswa Trust.

His expertise in community development includes experience with HIV, microenterprise, workforce development, disaster risk reduction, participatory research, governance and advocacy, and human rights.

Pingback: Saturday | A Pett Project