Global Communities’ David Humphries and I sat down to talk about our upcoming InterAction Forum panel, “Respect, Reality & Responsibility: How to Communicate Global Development with a Double Bottom Line.” A condensed version of this conversation appeared on InterAction’s blog.

Global Communities’ David Humphries and I sat down to talk about our upcoming InterAction Forum panel, “Respect, Reality & Responsibility: How to Communicate Global Development with a Double Bottom Line.” A condensed version of this conversation appeared on InterAction’s blog.

Jennifer Lentfer: What is the state of the “development discourse” in your opinion? How can communicators create a more robust dialogue, embracing criticism and inviting debate?

David Humphries: As with global development more broadly, development discourse is in a state of flux. We are all asking questions about our role in relation to the private sector and emerging economies in this post-recession world. At the same time, many organizations are still pushing out the traditional fundraising-type communications – starving poor kids who desperately need our every dollar. Others are focused on every innovation, as though each solar panel and mobile app is the latest solution to world poverty. Many want to motivate their grassroots followers but hide from those who criticize global development. What works and what does not?

Communicators are influence professionals. We can use our skills to convince people to give us money and to reassure our friends. But we can also use our influencing skills to convince the people who hold the purse-strings and who may even be our traditional opponents to understand development differently. I vote for the latter as being more important.

How do we do that? What are some examples of the best and worst types of development communications you’ve seen?

Jennifer: This is an exercise that I have asked my students at Georgetown to do in my International Development Communications class, so I have examples up to my ears now! The worst types of development communications I’ve seen have a distinct “othering” element to them – people are victimized and exotified and portrayed as nameless and powerless. Their role is only to be “saved” by the generous benefactors living in rich countries. Not only is this type of communications antithetical to the mission of international organizations, it is racist, classist, exploitative, and immoral.

The best types of development communications are ones in which the role of people in developing countries to affect their own lives and circumstances is at the center. This is not the pure “pulling oneself up by their bootstraps” narrative, but rather a more engaging and nuanced approach to portraying how the circumstances that place and keep people in poverty are changed.

It’s about capable and skilled individuals having and making new choices. It’s about how communities band together in mutual support and cooperation. It’s about how movements are formed to demand change from those in power. When international NGOs and foundations get this right, they place themselves no longer at the center of this change, but they transparently discuss the resources that they bring to the table and how they support their partners and contribute to the efforts of everyday citizens.

My question is why we see the same narrative structures used by most INGOs over and over again? Why aren’t more organizations aptly representing the complexity of the issues we face?

David: Just like Hollywood, we like to rely on the same old stories that we know will bring in the money, and just like Hollywood our sector also produces a lot of garbage. It’s hard to be brave – how can we justify investing resources in something we cannot prove will work? I would love to see all of us pledge to invest 10% of our communications budgets in using radically different methods then sharing the results so we can justify taking a different approach to our bosses.

Communicators need to learn how to interact with data and leverage it to help influence evidence-based decisions by the people who have the money and power to make a difference, be they proponents or opponents. I have a lot of respect for the work of Innovations for Poverty Action and Chris Blattman.

And from the flipside, the people who report on global development, I have been impressed by the work of the urban-focused Citiscope, which takes a “solutions-based” focus, countering the “problems-based” focus of most media platforms today.

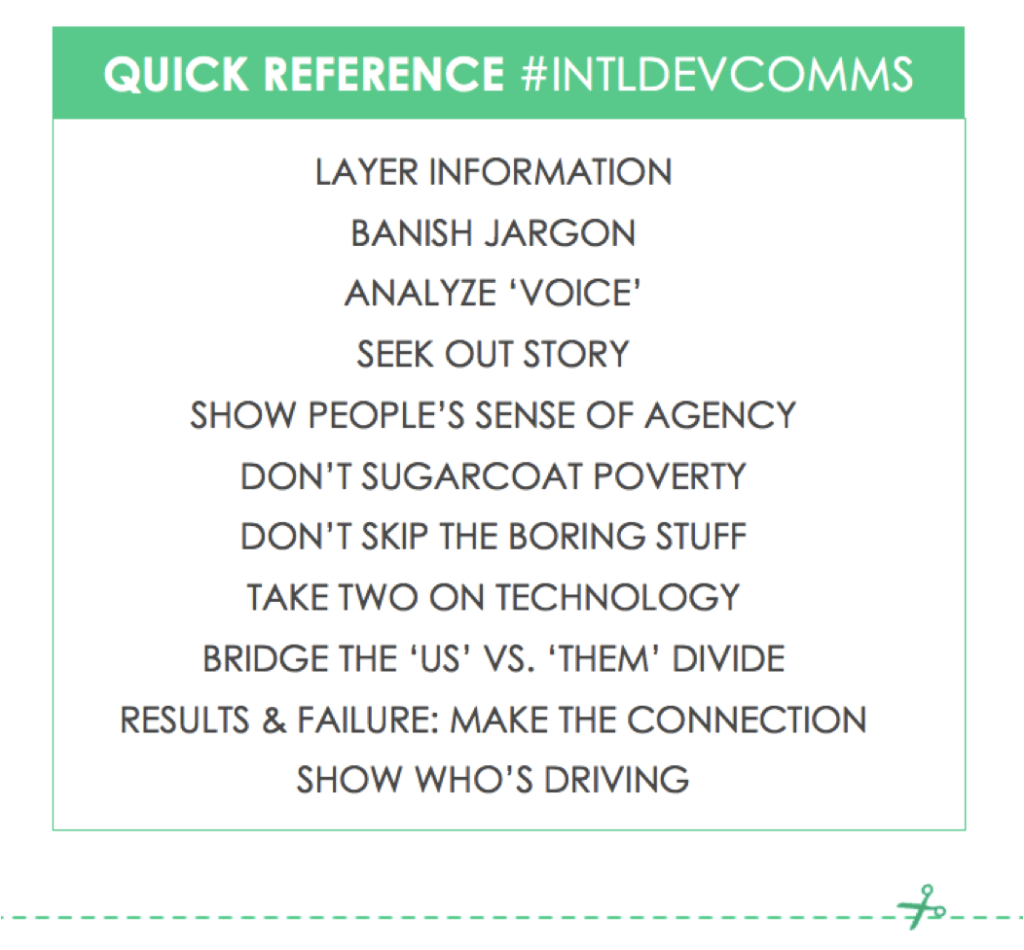

Last year, you published an online guide to communicating effectively and respectfully, called The Development Element. If there is one piece of advice above all others that you would ask all development communicators to remember, what would it be?

Jennifer: Take more risks. Try new things – new kinds of narratives, new platforms. What you said, just try. Get feedback. Adjust your approach/messaging quickly. Then try again.

Communications is no longer just a functional “service” to an organization’s fundraising department. It is central to how an organization achieves its mission. Therefore larger institutions and “old school” organizations need to learn how to break down and let go of approval processes that delay and complicate the ability to iterate new ideas and content.

Do you think that the very nature of our jobs as global development communicators is changing?

David: If your job isn’t changing, then you’re doing it wrong. I’m friends on Facebook with people with whom we work—we used to call them beneficiaries—but thankfully Zuckerberg didn’t give Facebook a “beneficiary” friend setting.

As the world changes and the business side of global development changes, we have to adapt to that and work out where our organizations fit. We should not cling to old methods and old business models, but embrace the changes around us. As communicators, our role is to help others understand the role of global development. So if you are communicating in the same way you did in 2008, expect to be out of business soon.

But to me, here’s what does not change. I don’t think we are in global development to force our worldview onto others, but rather to come to an understanding of theirs, and then work together for the best solution to intractable problems. It’s a partnership, regardless of how the world changes. As long as we remember that, we can’t go too far wrong.

Access to communications technology and social media should at the very least embarrass us into doing a better job of telling people’s stories.

Jennifer: What you wrote in the Guardian, that “we must be able to face people [in developing countries] knowing we have told their story how they would have it told,” is a mantra I’ve shared a lot in my work.

David: Unfortunately I think the portrayal of “voiceless” and “powerless” people will continue for some time, partially out of less well-informed good intentions and partially because it is good for business. But as people become better informed, and as consumers change as a byproduct of access to communications technology, this portrayal will be retired.

Jennifer: Why do you think there’s such a polarized view of global development – as all good and virtuous or all bad and wasted – among the public? What role does our sector have in changing this narrative?

David: I’m not sure it is totally polarized, but you would certainly think so from the media and publishing industry. If Dambisa Moyo wrote a book called, for example, “Certain Forms of Aid are Very Effective, but Not Government and Multilateral Cash Transfers,” I don’t think it would sell as many copies as the ominous “Dead Aid,” even if it would be a more accurate description of her argument.

A lot of the problem is that both proponents and opponents of development assistance exaggerate their claims for economic reasons. Media editors do the same, and then politicians piggy-back on these claims because aid – giving money to foreigners – is a political football.

If you are selling a product, you are rarely approaching a topic with intellectual honesty. I think the best answer for our sector is to get together, close the doors, kick out the business managers and the PR people, bring in the evidence, and hammer out the closest thing we can get to clear answers. The more we know about what does work, the better we can shape our work to the evidence.

Ultimately, I think it’s more important to change what we do than change how we communicate it; if we are confident it works, communicating is a piece of cake.

I wonder, do you think overall development communications are improving or getting worse?

Jennifer: I think more than ever before, globally-engaged citizens in rich nations are looking for effective ways to affect change in the developing world, and they have more information at their fingertips about how to do that. That is, in effect, “upping the game,” of NGOs. We are embracing storytelling in our sector, and more and more organizations are rejecting “poverty porn.”

Within organizations, communicators are also waking up to how they can shape and frame the international development narrative – not to just make sure organizations are doing their best, but respecting, humanizing, and upholding the dignity of everyone involved.

Perhaps more importantly, communicators are recognizing the power of their platforms and are inviting more people to have a seat at the table, to tell their own stories.

***

Related Posts

11 useless approaches to communicating about global development

How to reframe the #globaldev message: Local organizations telling their own story

The power of the pen: Why I left M&E behind for communications

5 pulse-checks before clicking ‘publish’ on #globaldev communications

The double-edge sword of mass communications: Is stereotyping inevitable?