Some more reflections from teaching “Storytelling and Communicating for Change” last fall in the University of Vermont Masters of Leadership for Sustainability program. See my previous posts here.

Sorry, emotions win.

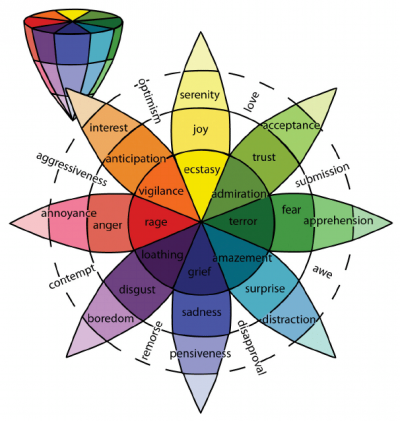

Our education privilege and organizational cultures tend to dismiss the emotive part of storytelling, and view emotion as having no role in rational decision-making. This can be expressed as a preference for objectivity all the way to invalidating people who show emotion. Our thinking minds have been trained that “hard” numbers and “objective” data is more important. We want to believe that logic trumps emotion. (And yes, I use that verb intentionally as politicians are SO skilled at using storytelling within their rhetoric.)

Gotta break it to you though…the evidence is in and it’s not true. Emotions win. MAGA anyone?

Cognitive psychology tells us that we look for data, to confirm what we already “feel.” That is why even if data is part of our messaging, it’s best to present it second, as its most important function in persuasion is to help people rationalize why they feel a certain way on an issue.

Now the good news about stories and storytelling is, that in skilled and trusted hands/mouth, they can contain pathos, logos, and ethos. And really, what isn’t biased? It is *really* possible to communicate without some measure of our personal perceptions, emotions, or imagination? Most days, it seems to me, neutrality is just a thought experiment rather than a lived reality. This is the stuff philosophers debate, but we communicators have to get some actual work done. (Ha.)

I’ve actually come to see the pretense of objectivity or neutrality as a vestige of white supremacy and patriarchy. The “logic” goes: the personal and emotional (which are a core part of building relationships) are irrational and should not be part of decision-making. What bunk! What the denial of relationships means is that power is preserved, unchallenged, and anyone who shows emotion is invalidated.

The real question is who gets to show emotions in our organizations? (Hint: It’s often related to power.)

Whole people, fuller stories

Usually stories are told from only one person’s perspective. Imagine, even our own story about our own lives is only told from one perspective. How would our mother or our best friend or nemesis tell our story? It would be different… Portraying the wholeness of people – not just easily-observable-to-the-white/male-gaze characteristics – is vital. For example, people can be “reliable” and “poor” at once. People can be “salt of the earth” and “complicated.”

It’s impossible to capture the wholeness of any one person, especially when what you’re writing has to serve an agenda, investigate an issue or organization, or deliver on already-set expectations. I think that’s why it’s so important for organizations to declare their communications philosophy, so that all people within the organization can be on the same page and call each other out/in as necessary.

Manufactured urgency is one key barrier to fuller storytelling. It takes time for people to consider the implications of their decisions. And stories can be vehicles for people to consider consequences and be more inclusive. No wonder it’s not prioritized. Stories require people to slow down, and listen – not just achieve.

As a nonprofit communicator myself, my constant battle is to be true to that wholeness/potential, and invite well-meaning do-gooders to think deeper – and into healing. When I have experienced healing within relationships, families, and communities, the complexity of individuals and the potential of humanity emerges. Can we put this at the core of our content?

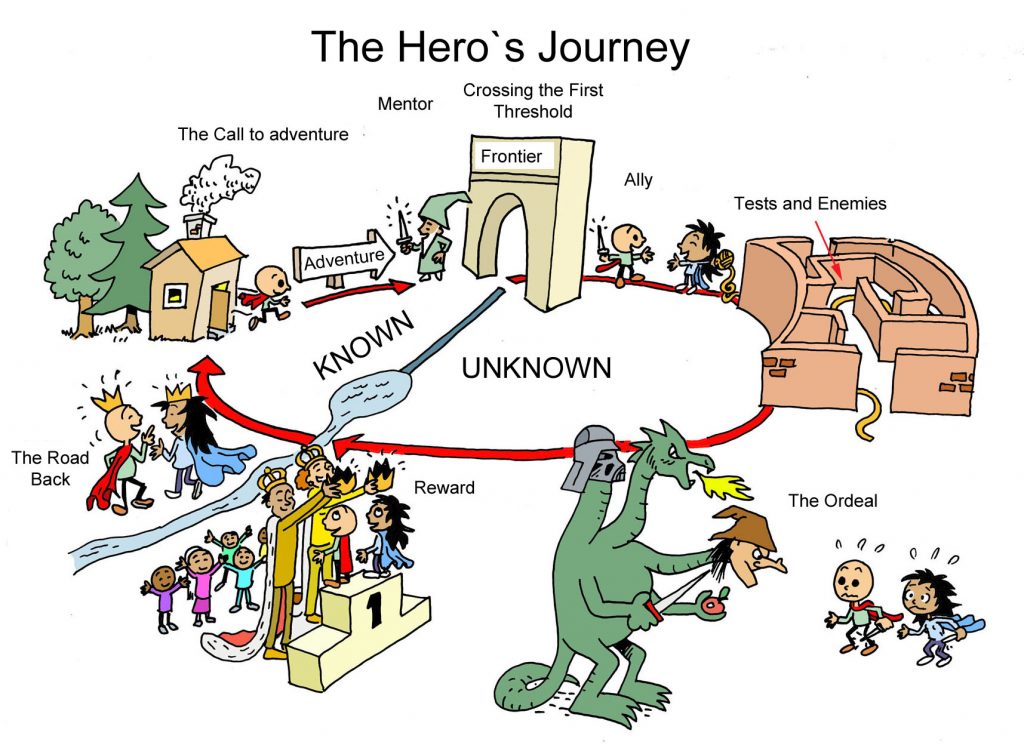

Reframing the hero’s journey

The constant use of the hero’s journey as a storytelling mechanism has an impact on people’s views of collective action as a social change strategy. If people continue to believe that they have to overcome risks/problems/obstacles on their own, this may just lead to more isolation and despair.

I’m more aware all the time of the falsity of heroship, as well as villain hood. One of my favorite set of questions of my nephews as we read books that portray this binary is: So why do you think so-and-so [villain] is acting that way? Who did you think so-and-so [hero] got help from?

Let’s portray our heroes as accountable, as cooperating, as being delegated to. Can our communications reflect that overcoming of obstacles or transformation (even within ourselves) cannot happen on our own?

Yes, individuals together make up the collective, so how else can the hero’s journey be altered?

When one is concerned with changing narrative frames, it’s important for discomfort to become a familiar character, not just during the journey itself but as an ongoing ‘normal.’ ~Corina Pinto

A hero’s journey’s lesson is not always found in the “resolution” of the conflict. If our storytelling represents our lived experiences in truthful ways, we can represent complexity and offer inspiration to find collective solutions.

Trust that the details can come

Are there times when there’s a need to be technical and delve into the complexity of an issue or situation, even if it is hard for general audiences to understand?

Not until you have an audience’s attention and commitment to action. And also when we’re sure the added technicality/complexity is serving the whole, not just our own egos and desire to be seen as “expert.” Before that, I believe it’s wasted breath/effort because being bold in our communications is key to attention-grabbing.

The details/nuance will have their time. Communicators rush to offer them much too often. Instead, focus in on what you want the reader to DO. Joe Schmoe on the street will never care about nuance the way you do. Ever. And it will certainly never drive anyone to take action.

Is it more important that the reader understand everything that you do? –or– Is it more important that they are attracted, invited, engaged (in what are fleeting moments devoted to reading something)?

***

Related Posts

Reimagining Nonprofit Communications in a Hyper-Connected World