A guest post by Marc Maxson, Innovation Consultant at GlobalGiving.

In Jennifer’s previous blog posts, several people offered their answers to the question: Why do aid projects so often fail?

Chris Etuka Obinwa: People are not involved in design or implementation. The idea doesn’t fit the local need. It’s not sustainable.

Barongo ba Kafuuzi Ateenyi: People are not involved because they lack a voice. Experience has taught them that their voice doesn’t matter.

Njoroge Kabugu: Local people know the solutions to our problems to begin with, so local people ought to provide the services that international NGOs do.

Now why aid projects fail is a big, multifaceted question. But I think I can shed light on why we seem to go in circles around the answers. In order to say more, I need to explain where my answer comes from.

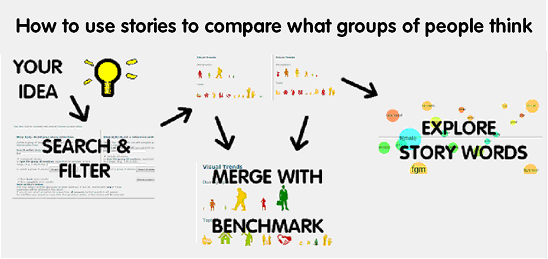

From 2010 to 2013, GlobalGiving’s network in East Africa collected tens of thousands of narratives about any “community effort” that a citizen had been involved with. And while these narratives are not the whole story, I think they better reflect the opinions of the people than experts do. I’ve developed online tools that allow you to lump these 57,000 stories into collections for just about any question, and extend the data to cover your specific group or area, using this process:

So to gleam insights into why aid projects often fail, I chose to categorize our thousands of “failure” stories into two storyteller perspectives: In both cases, the storyteller shared a story about an outside group coming, helping, or supporting them. But in one group, the storytellers felt affected by the events, and in the other group, they felt they were involved in making the events happen. (These “involved” stories serve as the reference, or benchmark collection to which the “affected” stories will be compared.)

There are three times as many stories about people “affected” by events as those “involved” in the community efforts they talked about. In fact, across our 57,000 stories, only 1 in 8 storytellers felt “involved.” Comparing the “affected” to the “involved” narratives, I see:

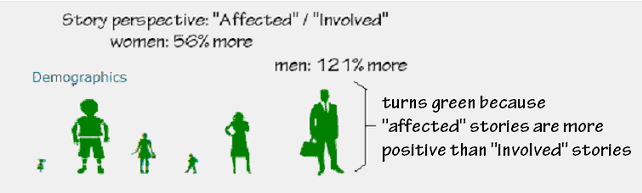

Adults, particularly men, are more likely to share the “affected” perspective than children and youth. Boys are more likely than girls. And though both of these perspectives are much more negative than the stories observers share (data not shown), people who are merely affected by the failures of community efforts are more positive than those who actually got to play a role in a failed effort.

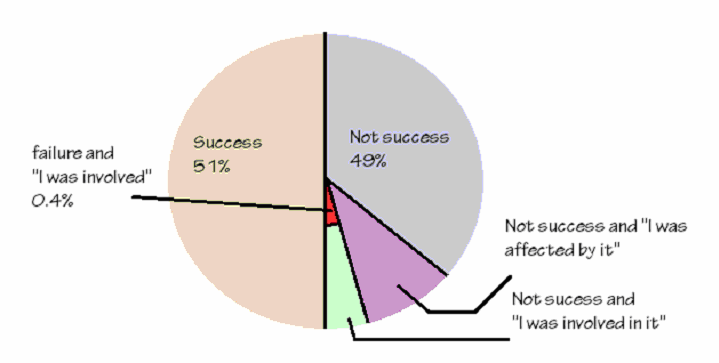

I believe talking about negative outcomes is a good thing. We learn from our mistakes. We use more cognitive, introspective words, and we ask “why.” People do this less often when things work. But this rarely happens at all. Only 0.4% of all stories use cognitive words like “think” or “believed” and reflect on the events. This supports what Chris Etuka Obinwa argues, that we need more people more intimately involved in community efforts and we need them to fail more often, reflect, and give feedback.

In the center of this is where we find the real opportunity for learning:

To have only a few hundred stories where real learning can happen out of 57,220 says a lot about what citizens have been taught. They’re used to being ignored and they’ve stopped searching deeply for answers, as Barongo ba Kafuuzi Ateenyi notes. But this same data set can also be used to look at the way people use reasoning, introspective, cognitive words in their stories. This blew my mind:

As our sample Kenyan and Ugandan storytellers gets older, they become less likely to tell introspective stories that ask “why.” Men and Women over 30 are about 50% less likely, and boys and girls under 16 are about 50% more likely. Everybody who introspects is more negative, consistent with what the author of The Secret Life of Pronouns, James Pennebaker, predicts.

Maybe the aid world’s obsession with “happy stories” is precisely what drives us away from learning what we must before we can succeed.

And I believe Njoroge Kabugu is also right. A quarter of all stories are about solutions, not problems. In stories about failure, half talk about a solution. We included this problem-solution question precisely because we thought local NGOs would want to learn from solutions stories.

But we are both the citizens and the “problem solvers.” Our bias against thoughtfulness is personal (citizens) and systemic (organizations). Very few organizations have made an effort to do what I just did in this post.

I’ve developed these online tools to show you life, richly encoded in narratives and understood on a scale that has eluded the aid sector for decades.

All of the tools I used are free and online, and rather extensible. We even reward our GlobalGiving partner organizations if they use them.

In fact, the Nominet Trust has funded us to provide intensive storytelling-grantwriting training to organizations that are curious enough to make better use of what already exists. If you would like to join, our application deadline is a few weeks away. Learn more and submit your expression of interest at www.globalgiving.org/storytelling/.

And even if you miss the deadline for the training program, our tools will STILL be free, online, and come with extensive do-it-yourself tutorials at that same link.

The more your dive down this rabbit hole, that is GlobalGiving’s Storytelling Project, the more I think you’ll find practical ways to amplify your organization’s vision and build a real relationship with the people you serve.

***

The search tool, for beginners: http://djotjog.com/search/

The compare tool, for the truly curious: http://djotjog.com/compare/

Pingback: Why aid fails (syndicated on how-matters) « Chewy Chunks

Love this blog, and this post. I am a big fan of failure stories.

Your project in General is also very cool. I have many questions about it… I’ll need to check out your website. How do you deal with translations? That could really affect your results, in terms of words used.

Questions on the pie chart… I assume all those subgroups are a breakdown of the 49%… What then is the biggest section of the 49%? (Not labeled). Also, I think that people will be quick to say that if people are “involved” a project is less likely to fail, but I think also that no matter the outcome, if people are involved they are less likely to report it as a failure.

We can’t forget that objective indicators of success are still important too. (Did the project deliver a service? Yes or no.) Don’t get me wrong, your project quantifying and highlighting theses stories is really important and cool, because we don’t do it enough and we can learn a lot. But can you correlate with more typical indicators of success?

Keep up the awesome blog and work… 🙂

Dear “T”,

If “objective indicators” of success were more than a fantasy, we wouldn’t have been debating how we define success for the last half century.

Indicators are subjective. They are fed by people counting objects, and these counts have always lied, because not everyone benefits when the numbers are accurate.

I have found (begrudgingly) that extracting data from large narrative collections is a less complex process to manage than defining and tracking sets of indicators. One narrative and a few simple survey questions will provide you with “enough” to see common patterns emerge from many perspectives, and “enough” to hear a community speak above the noise of individual perspectives. It is also much easier to detect and correct for bias in narratives, as explained in The Secret Life of Pronouns. Deceptive stories leave clues, whereas tidy numbers can cover up a lie. In fact, the problem with number-centric monitoring is that the data is rarely comparable and difficult to aggregate. This approach can “fix” the statistical “power problem” in the aid world, as narratives put the focus again on collecting as many perspectives as possible, asking questions in an open-ended but benchmarkable way, and tracking learning from data over lauding the numbers themselves as the “answer.”

The best way to see the limitations of “standard methods” is to try using this tool to prove/disprove oft-debated statements by experts.

For example, it turns out that among the “involved,” people are equally likely to be introspective regardless of whether they discuss success or failure (26.8% versus 27.6% respectively). So while you are correct in asserting that “if people are involved they are less likely to report it as a failure,” those who ask “why” and use cognitive words do so at the same rate regardless of the outcome. By flipping the filter (thoughtful vs involved), I’ve re-sorted the data in way that allows us to get unbiased feedback. Little tricks like this will ultimately be part of the solution, because our current M&E system allows us to fool ourselves too often.

Pingback: Examples of meta stories from narrative analysis « Chewy Chunks

Pingback: How organizations are adopting the storytelling method to their local context « GLOBAL CRITICS