I’m sharing an interesting discussion that’s been going on via the LinkedIn Africa NGO Network group, “Why is development aid having corruption problems in Africa generally?“. Some of the key contributions on root issues follow below. Unfortunately they are important issues not heard often enough in aid effectiveness discussions. I offer this food for thought for aid workers and do-gooders alike.

***

Dr. Chris Etuka Obinwa (Researcher): The people at the grassroots in the home countries are not involved from the takeoff stage to the conclusion of the projects. Secondly, the policies designed are at variance with the home countries policies. Thirdly, lack of sustainability of most projects. These create a huge gap which those involved take undue advantage of.

Godifri Mutindi (Learning Advisor & Consultant): The agency theory shows that people naturally chase their own [interests], rather than other people’s or even the group objectives. Going back to traditional Africa, the community welfare system, which was to take care of orphans, was abused. Philanthropists take advantage of this goodwill from the public—that they are people who want to improve the marginalised’s welfare and chase their own interests. History has shown that even religious movements (those who are supposed to be the greatest philanthropists) and the socialist governments are very corrupt. When there is little accountability and transparency, especially in Africa, this is a recipe for disaster.

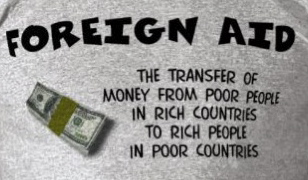

Poverty is big business all over the world, not only in Africa. In this big business, where billions are poured by donors and bilateral partners, governments (through well-connected officials) and NGOs (including international ones) have a big party. Are these entities, who abuse and enjoy poverty-related resources, particularly interested in solving the real problem—poverty, ignorance and discrimination?

Poverty is big business all over the world, not only in Africa. In this big business, where billions are poured by donors and bilateral partners, governments (through well-connected officials) and NGOs (including international ones) have a big party. Are these entities, who abuse and enjoy poverty-related resources, particularly interested in solving the real problem—poverty, ignorance and discrimination?

Jennifer Lentfer: The problem persists because local civil society organizations are currently the lowest common denominator of international development assistance. I think it’s time to recognize local initiatives and indigenous organizations as vital to supporting demand-driven development that can genuinely challenge power asymmetries, and unleash social change.

We continue to witness Southern organizations or “partners” being rebuilt into more professional organizations that lose their character and represent only the interests of the community that align with funding or Northern NGO guidelines. This should ultimately lead us all to ask – whose interests are really being served?

Dr. Tererai Trent (Senior Evaluation Consultant): Jennifer and Godifri you both speak to the heart of the issue. I wish such discussions could be part of the dialogue when policies are being instituted. Hey, it’s time to recognize the vital role that can be played by involving local grassroots organizations. It’s sad but in the name of ‘expertise,’ indigenous organizations have remained in the margin, and left to receive the leftovers, and yet, these local organizations hold the key to sustainability.

Godifiri, you raise a critical point—the disappearance of the community welfare system, and yet, the Northern friends speak about cultural appropriateness, empowerment, participation, collaboration and all those money-making-catch phrases. I know there is no justification for corruption. But unfortunately an unintended recipe is being created for it.

Thanks Dr. Atuka for highlighting the implications of conflicting policies. So the question for me is; those of us who would like to see change, what is it that we can do beyond airing our views?

Jennifer Lentfer: We all know that currently there is a large discrepancy between the resources that are mobilized or acquired by donors, governments and international organizations for global development, and what percentage of the money actually reaches communities and local leaders. I am working to advocate for far-reaching and responsive small grant mechanisms that will support local indigenous organizations to assist communities to become more adaptive and resilient, and building civil society in the process. People, under the direst of circumstances, can and do pull together. My hope is that the relief and development aid sector can finally recognize this.

Godifri Mutindi: We have to agree on the meaning of ‘corruption’ in this industry. Besides obvious cases such as embezzlement of funds and fraud, which are common in developing countries (but much more developed in the West), what about:

1. The racist and nationalist employment policies of international organisations, especially at top management level. It’s almost a law that an NGO from such a country has to have the Country Rep, Finance, Operations and Project Director from the same state or at least, of pale skin. Many a time these so-called specialists have very low qualifications and are appointed through connections.

2. Very large gaps between the locals and the expatriate conditions of service, even for people with the same qualifications. One cannot stop wondering how an organisation using the US$ pays its personnel in local currency and denies them a decent living.

3. Top-down management, even for rights-based approach’ organisations. Jennifer has already expounded on this. There is no engagement and consensus on issues. The expatriates and a few handpicked nationals generally agree on self-serving policies and report these externally as the developing countries’ consensus.

Jennifer Lentfer: Thank you for expanding the definition of corruption in aid, Godifri. I always think it is ironic that INGOs never look to themselves as contributing to the fraud and embezzlement. Where is the self-reflection among donors about each layer of bureaucracy taking their share of the aid funding before it ever reaches the ground?

Njoroge Kabugu (Student and blogger at The Bigger Village): I do agree and would also add that we as an African people do know the solutions to our problems to begin with. Can we not form or support local and national NGOs that are run on ethical principles, and also that push for public policy that will strengthen the NGO sector? I know we have organizations that can dig wells, construct schools, provide financial services etc. which, if there were the right policies, would be used at the national level to provide those services that the international NGOs do. When a donor gives a grant in the US, they do not have one of theirs employed to follow the money. The same should follow for Africa.

On another note we in the Diaspora also need to support our NGOs in Africa. We can create an umbrella organization that can influence public policy, set ethical standards, monitor local and international aid, exposing corrupt practices by both the local and international NGOS, as well as providing funding to organizations on the ground that are up to par on how they conduct business.

Godifri Mutindi: I have heard an interesting story about African professionals. They are compared to crabs in a pool, which want to climb onto a rock, in order to get out. Each one of them wants to do it alone, thus loss of synergy. Actually, when of them starts climbing, the other ones bite the leg and pulls them back into the pool! To them, it’s ok to suffer together, rather than seek a unity of purpose or support those who have the determination. I wonder if this analogy is true or to exaggerated.

But check our politics, education, football and even religion—there is an unmistaken egoistic thread running along. We easily divide ourselves into national, religious, regional, ethnic and racial blocks. (I don’t want to believe someone manipulates us). It seems as if the educated African has greatly failed his continent because the exploitation and corruption (the matter under review) is not done using illiterate people. Our own graduates, whether in government or NGOs, benefit and collaborate in expropriation of poor and marginalised communities of the resources meant to uplift their lives. Please, read the late Ken-Saro Wiwa’s political sattire, ‘The Prisoners of Jebs“.

But check our politics, education, football and even religion—there is an unmistaken egoistic thread running along. We easily divide ourselves into national, religious, regional, ethnic and racial blocks. (I don’t want to believe someone manipulates us). It seems as if the educated African has greatly failed his continent because the exploitation and corruption (the matter under review) is not done using illiterate people. Our own graduates, whether in government or NGOs, benefit and collaborate in expropriation of poor and marginalised communities of the resources meant to uplift their lives. Please, read the late Ken-Saro Wiwa’s political sattire, ‘The Prisoners of Jebs“.

F. O. (Monitoring & Evaluation Professional): Well, development aid corruption is just a song played and listened to in Africa in general. The cause of this is just centered around [what] I would generalize as expressed by African leaders as “dark-hearted national power interests“. This is where we should start from. In Africa, it is common that leadership is characterized by selfishness, which is perpetuated by direct and indirect promotion of ethnicity. This is through provision of social, political and economic privileges to particular groups of people.

Divide and rule technique is applied to break down linkages that easily topple ruling governments. [It] is applied because they are aware of the fast moving waves of formal education across their societies? [This] style of leadership is what you find up at the top to the grassroots in Africa. These have all broken down the African traditional systems discussed by others and this has been existing for a long time. It is thus not surprising when aid is misused in such societies. Africa still needs leaders with vision like Mandela—a leader who can set an example that will later impact on the social, economic and political development of a nation.

***

When I asked Dr. Trent if she’d be willing to include her comments in this post, she went on to share the following, which leave us with some important questions to consider going forward:

Dr. Trent: I am so surprised that many of us fail to see the continual perpetuation of [a] colonial way of approaching development in Africa. This is not a blame game, but reality at its core. In most African communities people are used to see[ing] the West bringing aid. They get excited, women ululate and the men clap hands because their expectations for a better future are raised, and then everything disappears like rain. Who gains and gets empowered in this process? Outsiders’ resumes and curricula vitæ are powerful and rich, and yet, ‘the insiders’ resumes are empty and labeled with corruption and laziness. Whose reality of development is it?

The dependency syndrome which comes with aid and the “stereotypes and assumptions of who poor people are, what they need, and how they can be helped” fails to recognize peoples’ intelligence, strengths and resilience. Mechanisms for accountability are one-sided and built upon mistrust.

As aid deliverers why are we failing to confront our own stereotypes? Why do we ignore the sovereignty of these communities we say we help? Why do we bring to them frameworks and approaches that work elsewhere without questioning their validity? Should the Western epistemology, ethics and concepts be the main default lens for development in Africa? (For more information on this topic, see my post on the Genuine Evaluation blog, “Where and Why Western lenses miss the mark in Africa: The case of HIV/AIDS prevention evaluations”.)

More[over], where are the local indigenous experts? Are they included in major think tanks, or is their inclusion more of a perfunctory effort in order to deflect criticism or comply with some rules? Are local experts actively included in the decision making of aid and how it should be delivered?

***

Related Posts

Trocaire: 10 things INGOs need to do

Confessions of a Recovering Neocolonialist

This is a great article that addresses some difficult realities. People don’t realize that many policies and strategies regarding Africa are very arrogant and condescending.

“Understanding Africa for Dummies”

http://www.twitpic.com/2910br

This is a great discussion. I like the questions posed forward by Dr.Trent and others. To me, international NGOs often times assume to know the problem of those they want to help without consulting the people in need. They believe the people in need especially those in Africa have no option and their own model could be a panacea to their problems. They fail to recognize the ethical justification and validity of their acclaimed working-model in Africa. I could remember using a theory/model which was successful in most American Countries to the same situation in South Africa. I found out that this model cannot work successfully in South Africa until some cases are included. I could see that humanitarian aid (especially in Africa) has changed and it is now seen as a business venture by some NGOs. My view is that humanitarian aid should be directed towards its original use without prejudice and discrimination.

Dear brothers and sisters,

I am very happy to reach all these reactions. I have always told my friends that people from the west cannot solve our people because they cannot feel it the way an African can feel his or her own problem and is in the position to profer the best solutions to our problems. We have got brains. My question is now, is it not hard time for Africans to learn how to take care of our problems ourselves without involving the international world?

Great minds, let us all see how we can put our human resources together to help our people. Right now please I want to make a national Conference in Nigeria as a post electoral process in Nigeria. The target group is children and women. My target is the next Nigerian election come 2015. To help people come to the knowledge of their rights and democracy and good governance. So please if you think that this interest you, do not fail to contact me as soon as posible. The seminar is planned to take place in Nigeria second week of November. Together we can create change. Big hug to you all

Additional comments can be found on the Peace and Collaborative Development Network, where this is crossposted: http://www.internationalpeaceandconflict.org/profiles/blogs/aid-africa-corruption-and?

Many good points made, but I believe that too much simplification and generalizing is being done. Fixing corruption is like doing “good aid.” One must look at the situation on the ground and adapt strategies to the context. Not all INGOs are colonialist, many are. Sometimes local NGOs are the answer, sometimes not. There is no silver bullet: one needs open, intelligent, critical examination of what is in front of you now and to address those immidiate, real problems without letting pre conceived ideas interfere.

It is not only aid and corruption problem that Africans are struggling with. Africans are generally struggling to globally become part and parcel of policies to help Africa. Furthermore, Africans are struggling with issues of recognition of their qualifications and contributions. It is important to mention here that Africans are the least hired in both the Bilateral and Mutilateral organisations, irrespective of their very good education.

Pingback: Bible and Mission Links 1

All of you -Mutindi, Trent, Obinwa, Lentfer, and Kabugu- have some good points, observations and questions which I agree with. I may add though, that vested interests and identity crisis are two things that will keep the ‘dirty water’ swirling and without getting flushed out. There are a lot of vested interests in most initiatives intended to build up Africa that everyone involved goes into such initiatives with the mentality ‘what is in it for me’. The sad thing is that this vested interest runs from our top level African government administrators, politicians, businesses people and policy makers, to the elder, women leader, youth leader, pastor and civilians at the village level in charge of or involved in ‘top down or bottom up’ development processes. To some extent, unfortunately, it feels like the Bible verse that says ‘there is no one is righteous…there is no one who does good [things], not even one,…and some will even kill you’ is true (Rom 3:10-12ff). And so, I agree with Kabugu that we desperately need men and women of integrity, who are hard working and well intentioned, to lead the process of building us up from both ends- village and national level.

Secondly, we are struggling with identity crisis in two ways. The rate and cost at which many individuals and families in Africa are becoming consumerists and pursuing indulgence, without stopping to think, is alarming. It scares me how many families are trying to live the Chicago/London lifestyle in our cities in Africa. They will do whatever it takes to get the big dollar jobs, even if it means letting academies, and nannies raise their children, to live the lavish life, and be adored by their friends. The dangerous effect of this is that many people in small towns and villages are trying to copy the lifestyle of the people in the city, who are trying to copy Suburban lifestyle. And so we’ll keep losing the original and important building blocks- language, family, culture, faith, simplicity, genuine laughter etc!

While I have been impressed by some of the advances we have made generally BUT a lot of the policies we’ve integrated nationally have been carbon copied from the West (which is not perfect either). Some of the ideals in our constitutions, some of the ways we approach and implement education, economics, health policies, among others are so Western –geared towards enriching big businesses and corporations. And so we will keep pursuing and integrating certain policies that will keep the rich-poor gap the way it is. So, how can we teach our children some great African values, and perspectives, and combine them with great Western values? Also how can we integrate great policies and examples from the West (and East) in ways that can build us up, advance our communities, promote love, compassion and unity?

What an interesting discussion, thanks! Having lived and worked.around SSA for 20 years, i marvel and weep at tbe pressure that “reciprocity” puts on wealthier and poorer, the asked and askers.

I also know the potential power of the local NGOs but too often they get the least capacity built, have the least time to deliver far too complex results and rarely lead project design, sadly.

Finally, most donors short timelines, need for quick disbursement and quick results exacerbated by racism and self-perpetuation often precludes the real partnerships that best serve african communities that would build their capacity to self- “develop”…thank you.

Great points. I just wanted to add a couple of things to consider:

1. The need for big INGOs and donors to take responsibility for their contribution to forcing issue silos and technical fixes, where local development workers are tied to one-size-fits-all approaches vs more holistic and homegrown strategies that are more effective. This also results in organizations on the ground having to compete with each other for resources by pushing their one issue/focus rather working collectively and supporting each other.

2. The fact that so many INGOs and donors give huge salaries, cars and expense accounts to local staff they hire, making it impossible for smaller, more community-based organizations with less resources to compete for quality staff.

International NGOs have become a foreign policy tool for their respective gvts and funders. They are so thick skinned that they do not care about the (negative) effects of their programmes on local communities. Iam working on transitional justice in Zimbabwe and recently noted that there are efforts by donors to scale up food aid in Gokwe district which has just had a good harvest. This boils down to lack of accountablity for the NGOs as the local communities can not hold them accountable. Neither are they part of the agenda which is set in the metropolis to fulfill western agenda. International aid organisations are the biggest threat to sustainable dvt in Africa. Their perseption, definition and undertsanding of justice and dvt is Eurocentric and we surely need some decolonial delearning process advocated by the Latin American scholar Walter Mignolo to enable us to decipher the colonial matrix.

Godifri Mutindi expands on the points made here regarding the considerable gap in pay between foreign NGO staff and local workers in an interview with whydev.org. Read it at: http://www.whydev.org/earning-a-wage-in-development-an-issue-of-corruption/

A very important discussion and I really appreciate the points raised by all participants.

In my opinion the biggest problems are the ones operating at the top

The problem usually starts with the undisclosed or biased intentions with which western powers make the specific provisions for aid in Africa. It sometimes appears as if, aid is aimed more at influencing and keeping tabs on governments and policies rather than addressing the heart of the problem they claim to tackle. Other times western aid agencies come with a judgmental pre-formulated ideas and physical interventions which have no bearing to agroecologic, socioeconomic and other such relevant realities and needs of the people they are supposed to serve.

Equally important is the general lack of national feeling and integrity on the part of political bodies and few elites (management and technical) engaged in the large scale corruption and abuse of resources revived on behalf of the greater population in dire need.

Those two issues (donor and local government accountability) are of priority importance and need to be corrected prior to directing attention towards any of the technical aspects of failed aid work in the continent. I believe that the other issues would naturally fall in to place if those two major agendas find a real solution.

This is to say that it would be much more easier to address other obvious but equally important problems like adoption of improved community centered and resource based approaches, better integration of indigenous welfare systems, sustainability etc if genuine intentions and accountability

Aidis neither necessary nor sufficient condition for development,

Foreign Aid: A Reality?

I would like to know what makes foreign aid real in a situation where aid agencies/donors send funds for development in the developing countries and equally help themselves from such funds through fat salaries and allowances in the execution of projects that medium level manpower in the said developing countries can comfortably and competently carry out with little or no orientation.

Pingback: Real Impact with Saeed Wame | Good Intentions Are Not Enough

Pingback: Earning a wage in development: an issue of corruption?

Pingback: Moving along on the do-gooder journey | WhyDev

Pingback: My Letter to PC | there is no utopia