This week I re-entered an aid “institution” after five years of working with small foundations and local groups.

After just two short days, I can’t help but be reminded of why I left.

I am once again surrounded by smart, driven, committed people. But unfortunately they are largely a group of people who are also exhausted, overwhelmed, and discouraged by fighting while propagating the very organizations in which they serve. From my still outsider’s perspective, it’s as if the system closes in and the perpetuation of the institution itself slowly, silently becomes what consumes people.

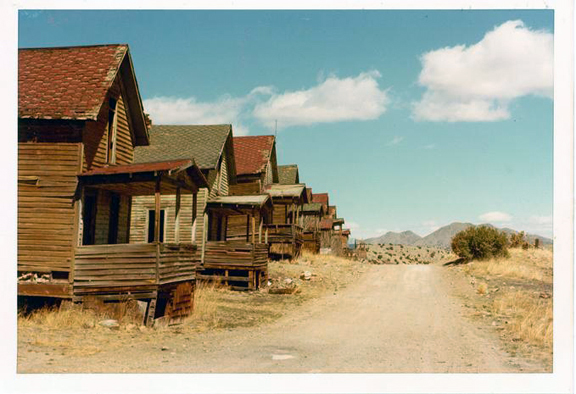

As I’ve sat in cubicles and listened to stories of obstacles and what’s needed and what’s wrong and “why I know this, due to all my years of experience”, what I picture of this institution in my head is not a grand cathedral, a revered edifice. Rather all I can picture is a deserted dirt road, derelict wooden buildings, and a tumbleweed blowing by—a ghost town.

The Community Development Resource Association in South Africa describes the “particularly undevelopmental global development industry” as characterized by:

- the need to urgently disburse money;

- a tendency to focus on product rather than process;

- higher respect for suits and ties than rages and bones;

- a proactive rather than responsive orientation;

- centralized and hierarchical decision-making; and

- bureaucratic and instrumental rigidities, practiced largely (if unconsciously) for the benefit of those who intervene.

The corporate culture of the large development agencies I believe results in many talented people spending most of their time dealing with the constraints of donor-controlled, project-based funding, which ties their hands and shuts down any possible processes that could result in local ownership and empowerment.

But we actually need to enable these same talented people to expand their attentiveness to how to change the rules and regulations by which their work is governed. We need these talented people to focus their roles on service and advocacy, rather than abstractions and bureaucratic technicalities.

Creative thinking requires an outlook that allows you to search for ideas, and play with your knowledge and experience. You use crazy, foolish, and impractical ideas as stepping stones to practical new ideas. You break the rules occasionally, and explore for ideas in unusual outside places. ~Roger Von Oech

But does creativity shrink, and is change more difficult, the larger an organization is?

I would like to see the large aid agencies examine and question the heavy accountability systems that take up most of their staff’s time, that marginalize and de-motivate people, and that ultimately do not lead to any real assurance of long-term results. Can aid agencies harness the energy currently focused on controlling finances and demonstrating “results” based on donors’ needs, and use it instead to concentrate on the priorities of those their mission ultimately serves? Or must protecting the interests of agencies always come first, given that they ultimately rely on fundraising from donors and the public at large?

Dylan Ratigan wrote a very interesting piece yesterday entitled, “This Thanksgiving, Occupy Yourself.” The following passage struck me as something that aid agencies may need to confront:

“You cannot know honesty without knowing deceit, good cannot exist without evil, and life is not life without death. Our challenge is to reconcile all of these forces as they all exist in each of us. Any institutional arrangement that denies this, that relies on images of perfection bereft of the shadow, will inevitably be dominated by the very forces of that darkness. Namely fear of the shadow, ironically.”

As Dov Seidman, author of “HOW: Why HOW we do anything means everything”, and Bo Burlingham, author of “Small Giants: Companies That Choose To Be Great Instead Of Big”, encourage those in business to do, I want to see aid agencies put behavior and relationships first. After all, they do not operate from a profit motive. They can change the game until the game doesn’t look the same.

Until then, I’ll be supporting and encouraging the seasoned and dedicated humanitarian and development practitioners from within these institutions to begin to openly, bravely, and constructively question “business as usual” in our sector. If not, they will continue to fight a tiring and frustrating uphill battle.

***

Want an illustration of an aid worker’s typical day-to-day? Most people I know did not get involved in aid to be a penny pincher or a paper pusher. Yet check out this excerpt from a position description I recently ran across. It struck me because this is what appeared before the sector or type of project was even mentioned!

Org X in Country X is looking for a Project Director who overall responsibility for leading and managing a Org X Project in Country X to ensure that the project achieves its intended impact. S/he provides strategic leadership and managerial oversight of the administrative, programmatic, technical, and operational aspects of the Project. The Project Director oversees the day-to-day work of the Project and is responsible for the effective use and deployment of staff and financial resources to achieve project targets. S/he is accountable for all aspects of the Project’s effective management, including financial and budgetary oversight, timely implementation of activities, and stakeholder relationship management.

Responsibilities include:

- Provide strategic direction of Project activities.

- Develop and update the Project strategic plan, ensuring that programmatic directions are technically sound, evidence-based and consistent with National priorities;

- Ensure that Project performance objectives and mandated deliverables such as technical activities, annual work plans and programmatic/financial/technical reports are carried out in a timely fashion and meet the highest quality standards;

- Provide leadership and direction to Monitoring and Evaluation strategies, frameworks, plans and indicators to capture project performance and results;

- Lead a periodic implementation review process to monitor progress and to identify specific actions that may be needed to achieve expected results;

- Employ appropriate management procedures to ensure that all resources are in place, adhered to, and in compliance with donor rules and regulations;

- Manage funds at local bank and approve expenditures in accordance with Org X and donor procedures, cost principles, and regulations;

- Partner successfully with Org X’s Senior Program Manager and Headquarters financial, technical, and operations backstop officers by providing accurate and timely reporting and updates on the Project progress and difficulties.

It has nothing to do with the organisations but the people who work in it. I have also been working for many organisations and also found out that people always need to praise themselves using the name of the organisation. Longtime ago I represented a very British organisation in Mali and my collegue from Burkina Faso told once “we are the best” and I told him in presence of all the other upperclass people, “no, only one of the better ones”. Competing and fighting and using poor Africans to show others how good they are. In that organisation worked also a Catholic sister from Zimbabwe and she told the Oxford-trained ladies sensitizing us with the gender-virus: “Look first in England how your working class women are living and after that tell us not that we in Africa have to become more gender friendly.” The English upperclass ladies felt so offended that they walked out and after that blaming the man from Holland who “influenced” the black sister from Zimbabwe. Do your work and look only at these class-driven intellectuals.

Hi Jennifer,

Another honest and thought-provoking piece from How Matters. Thank you.

I can’t help but notice my own (unwelcome) skepticism over whether large institutions can change….. I suppose this is why we have placed on our focus on empowering the individual @ Satori…. because after years of witnessing the failure of top-down approaches to changing organizational culture (remember, I was a gender mainstreaming expert before Satori!) people powered change– one individual at a time– seemed the only viable way.

That said, the argument for strong leadership where self-care, humility, and service are concerned is pretty compelling. Where are our role models for this is Aid? I feel we may have to look more toward other disciplines for this kind of inspiration, because our own heroes are still unsung. Though i feel they are beginning to make themselves known…

Your point on product over process is well heard over here…. and we feel it even in our own org when we see that what we are trying to achieve is fundamentality immeasurable…. or at least not in concrete, material terms. But this is an age old problem in development, isn’t it?

Good luck with your new position….. I guess that makes you an ‘intrapreneur’ now? 🙂

The issues raised by Jennifer and the comments that follow are very pertinent to understanding why so many interventions become reduced to a tick box of “activities” to be carried out with virtually no meaningful process. Part of the problem is the so called professionalisation of development interventions and more specifically the management thereof. Organisations are increasingly being obligated to adopt coroporate values and practices and are being engulfed by the the technocratic requirements of the funders. Solid community workers do not cope well with all the new requirements and buzz words and so in many instances “consultants” are employed to write proposals, structure the M&E frameworks, write reports etc. There are serious breakdowns in understanding community processes and creating the space to work with communities in a meaningful way. It is a very worrying state of affairs and will do little to bring about meaningful change.

As long as relationships revolve around transferring money and other resources from North to South, the pathology Jennifer describes is all but inevitable. The job advert says it all.

Take ‘aid’ out of the core equation, and different kinds of relationship become possible, including mutual solidarity in efforts to achieve social and economic justice for all.

Organizations are living entities. Of cause, they defend their identity, their purpose, and their very existence. In turbulent times this binds a considerable part of an organization’s energy. Bureaucracy is (among others) a tool to ensure that actions inside an organization are aligned with its goals. There is a place for creativity – based on a general acceptance of the organization’s goals and identity and targeting evolutionary change rather than disruptive innovations.

Private sector experience shows that we need organizations that are good at innovating, but that we need much more and much larger organizations that are good at implementing proven ideas effectively. I feel that the place of large aid institutions is in that implementation space. In this space operational efficiency is required. Therefore they are a bad place for “a lot of things should be done differently”-thinking.

One additional point: I have to admit that I am an outsider and that I have insight in only a very limited sample of aid organizations. But all I have learned about their processes makes me believe that they still have to learn the basics of (lean) management. Incompetent management can largely contribute to frustration of competent and creative people.

Thanks Jennifer for another beautiful insight.

It is important to continue to work towards a new paradigm where ‘changing the world starts from within’. A first step towards this may be to reflect and to look at our own psychological motives (at both individual and organisational level) for engaging in aid/development. It is the vision within that shapes our outside world. It is our values, attitude and the way we think, feel and act beyond ‘abstract ideals’, that construct our relationships and the projects on the ground. It is crucial to cultivate qualities such as creativity, encouraging people to think outside the box, opening our ears and hearts, and acknowledging that maybe that image of perfection that we would like to project is unhelpful.

I find that the most effective aid workers and organisations are the ones that are willing to be seen as they are. Learning not to be afraid to look at our own personal shadow side, as well as the shadow side of aid work is an important step towards ‘smart aid’ and towards the construction of a ‘learning organisation’. As Jung said the more that shadow aspect is denied, the more it will emerge in unwanted ways, and we clearly see that in the kind of humanitarian intervention that has lost its soul, in the fear of showing vulnerabilities, of acknowledging mistakes and power dynamics.

As individuals burnout, I think that organisations burnout too, and both often keep going aimlessly, driven by a sense of duty and guilt embedded in the very idea of ‘doing good’. I believe that a different way of being and therefore doing things is possible. In my work I see many humanitarian professionals who search for that way within in order to engage with the world in a more effective way. When HOW we do things unfolds from the honest awareness of WHO we are, with our strengths and limits, change within and out there in the world takes place.

Good luck in your new job, I’m sure who you are will have a positive impact on how things unfold.

Excellent post, Jennifer. I think the job description you posted speaks volumes. There is absolutely no mention of process and people! When I read job ads like this, my immediate reaction is not to apply for the position. Because if this is what the job sounds like on paper, well, that doesn’t bode well for the work itself.

I have been thinking about @Erich’s point carefully. I am wondering how large companies like Google or Apple have managed to remain innovative throughout their growth. Are they just the outliers or is there something there that aid agencies can learn from? These companies are certainly changing the game as they play it.

I don’t think that Google or Apple or other large companies with a reputation for innovation (Sony is another good example) are outliers.

But two words of caution:

. All large companies (and also large aid organizations) are innovative to some degree. Toyota or BMW are getting out new models of their cars quite often, the same is true for Procter&Gamble or SAP or . . But their objective is to improve proven products and ideas. And they are using superior marketing money and outreach to repackage other people’sinnovations and push them into the market. Point in case: The IPod. MP3 has been invented by a German research institute and you could buy MP3 players from other companies before the IPod came into existence.

. All large companies with a reputation for innovation that I am aware of integrate large parts of the value chain. At the end of the day, the number of people that are hired for creative work is probably below 5% of the overall headcount.

The economist Clayton Christensen has done some research on innovation. He differentiates between two types: disruptive innovation (shaking the status quo) and evolutionary improvement. According to his research, successful companies defend themselves against disruptive innovation generated by insiders (for good reasons). Disruptive innovation can only survive in startups and small guys.

Interesting related article: “Why People Secretly Fear Creative Ideas” http://www.spring.org.uk/2011/12/why-people-secretly-fear-creative-ideas.php