I am a U.S. Citizen. I am relatively wealthy and educated; in the vast spectrum of this planet, I am the 1%. I am literate and fluent in English. I have connections to hundreds of middle and upper class individuals who I can gain support and funding from. I have a supportive family. I have the ability to write grants in persuasive English. I have unlimited access to the Internet and social media sites; I know how to manipulate these platforms to market my own initiatives and endeavors, if so desired.

Most social entrepreneurs and non-profit leaders today who are granted awards by prestigious foundations, who are praised for their work by news outlets, who market their organizations effectively both online and off-line are like me. They have a distinct advantage.

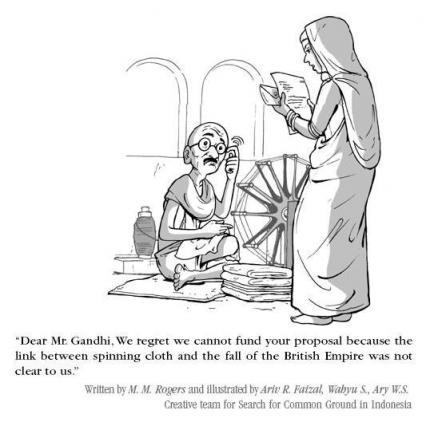

But community leaders and activists across Africa, Asia, and Latin America are doing just as much as American social entrepreneurs – if not more – to lift their communities out of poverty, to protect human rights, and to change the status quo. And yet, Southern activists gain little publicity in comparison to the many Western entrepreneurs who easily gain recognition after traveling abroad to do good. The difference is that Southern leaders face numerous barriers to raising funds and publicity for their work – barriers that their more privileged Western counterparts simply do not face.

Layers of oppression & marginalization

Unfortunately, leaders and mobilizers from oppressed communities – the ‘subaltern’ – continue to be marginalized in this game of fundraising. According to postcolonial theorist and Professor Gayathri Chakravorty Spivak, “the subaltern cannot speak, since s/he is required to be imbued with the words and phrases of western thought in order to be heard. Therefore, the subaltern cannot be heard because of the privileged position that academic researchers and development consultants from the North occupy.”

In fundraising for development work, these marginalized groups and leaders are not heard. Many barriers exist: language, as many grassroots groups have difficulty communicating their work in English. Competing needs, as the needs of grassroots groups sometimes do not match up with the defined priority areas of large foundations. Access to technology, because many small organizations do not have access to computers or Internet on a regular basis. And access to knowledge of traditional funding mechanisms used by donors including report writing, monitoring/evaluation, budgeting and finance. Groups are forced to “Westernize” and adopt Western language (English), internal organizational structures (hierarchical structures, formal non-profit status), and technology to gain access to the same resources.

Unfortunately, groups that are unable to conform to these standards – particularly those in rural areas, or organizations and collectives formed and led by the poor themselves – are often left out of mainstream development efforts.

How can we begin changing the status quo?

- Foundations can reduce the barriers preventing small, grassroots groups to apply by:

- Accepting proposals in different languages

- Simplifying proposals; reducing the number and complexity of questions

- Seeking out grassroots leaders and effective small groups through word of mouth and physical visits/meetings (not just paper proposals)

- Keeping monitoring and evaluation simple, with a few basic questions

- Encouraging organizations to share stories in the way that fits them best, rather than fill out complicated charts and tables

- Popular social entrepreneurship funders should question their approach of targeting mainly Western leaders, rather than seeking out grassroots leaders from around the world who are already implementing effective models in their communities.

- Funders can also supply small local NGOs with not only financial help, but also consulting assistance and training. Small, grassroots NGOs could benefit immensely from free consulting services and training in writing grants, fundraising and reaching out to donors, financial management, and marketing/communications.

Some examples of effective Western funders, in my experience, are Ashoka, which has done an excellent job of selecting and promoting less-known entrepreneurs and community leaders from around the world, particularly those doing effective work but lacking recognition. Another example is the Global Fund for Women, which focuses on funding small women’s groups that often do not have access to other sources of funding, and which have demonstrated leadership by grassroots women. The Fund imposes few reporting requirements, and allows funds to be used as meets the group’s needs, including for core operating expenses.

What do you think? How can funders reduce power imbalances and enable groups and leaders from marginalized communities to be heard?

***

(Note from Jennifer: Let me try to refrain myself from the cliché “this is one young person who is going places” routine, but I had the pleasure of meeting Akhila a few months ago before she left Washington D.C. to become a travelling-to-Afghanistan, California-loving, soon-to-be Harvard law student. She is a technical advisor and fundraiser for Justice for All, an Afghan non-profit that works to expand legal services and awareness for women and girls. Don’t miss her blog posts on Journeys Towards Justice—not just a good read, but a must read for all do-gooders.)

***

Related Posts

Does aid need a 12-step program?

“With the available resources we had…”

Reaching Girls at the Grassroots—A Sound Investment

Capillary Philanthropy: Businesses, local NGOs, and the future of aid

The elephant hasn’t left the room: Racism, power & international aid

Well done Akhila! for whatever you do. I am a lecturer of solid/ hazardous waste engineering at Kenyatta University in Kenya. Am in process of setting up a nonprofits/ TRUST to promote and add value to Municipal Solid Waste management through use of advanced technologies in about eight Eastern Africa countries cities. I would, therefore kindly request you to be connected to my network, so that you can advise and assist in fundraising. Let me know your thoughts.

Best regards

John Gakunga

Foundations can reduce the barriers:

1)Encouraging organizations to share stories in the way that fits them best, rather than fill out complicated charts and tables

2)Funders can also supply small local NGOs with not only financial help, but also consulting assistance and training. Small, grassroots NGOs could benefit immensely from free consulting services and training in writing grants, fundraising and reaching out to donors, financial management, and marketing/communications.What about that?

Kind regards

John Gakunga

Pingback: The westernized nature of the #socent industry | Journeys towards Justice

Thanks so much for hosting my thoughts over at your space! Looking forward to further conversation, discussion & learning as always!

Well-said, as always, Akhila. I especially like the idea of accepting proposals in different languages! Jennifer, your introduction wasso lovely and true as well!

Great post! A way we’ve been exploring at InsightShare is to use Participatory Video to send video proposals to donors, and also as an M&E tool, making it more accessible for people to portray their ideas, impact & stories in their own language. Check out here for examples: http://www.insightshare.org

John, I would be happy to speak with you via email and provide any thoughts or suggestions on fundraising if it would be helpful! Please feel free to contact me at: akhila.kolisetty@gmail.com. Looking forward to hearing more about your initiative!

Solemu, That looks like a fantastic initiative! I am so excited to see how it can be used by groups to share their stories in a more participatory way. How exciting!

Roxanne, Thank you as always for your kindness!

Thank you for this article, such things have gone through my mind as I have crawled through mounds of stuff that donors expect NGOs to be able to process just to be considered for a grant they may not have a hope in hell of getting.

As a native English speaker with some experience of writing proposals, I find that donors are often not willing to make any provision for the proposal to be written in the first place, let alone for the writer to attempt to pass on any of the skills necessary for the NGO to ‘develop some proposal writing capacity’.

But most grants are biased by the very difficulty of writing a successful proposal; small and even medium sized NGOs are more or less guaranteed to stay small. Big grants, on the other hand, are likely to go to bigger NGOs, so they can stay big. They, being big, have the capacity to write ‘winning proposals’.

I agree with your suggestions and I would like donors to see the proposal writing process as involving developing relationships over a long term, where NGOs with potential are recognized as such, and not squeezed out in a competition that has already excluded them before they start.

If donors don’t play a significant part in ensuring that smaller NGOs develop the capacity to compete for grants, it will just not happen for many good organizations.

Lengthy procedures also mean a lot of money is spent on the very competition that has already excluded the smaller and often more needy organizations. The mounds of paper filled in by organizations must also have to be processed by the donors, aside from the applicants who clearly don’t meet the criteria.

So maybe donors could reconsider how they spend some of the money allocated for these expensive competitive processes, even how they carry out their selection?

Wonderful post, Akhila. As someone who has ready many (many!) project proposals from budding social entrepreneurs, I am well versed in just how limiting the procedures can be. You offer some wonderful suggestions to change this.

I agree that procedural changes like accepting budgets in local currency, reducing notification times, accepting reports in local languages, etc. are all important “low hanging fruit.” They make it easier for grassroots folks to access funds controlled by donors. But we also need to go further and question why donors are controlling the funds, and according to whose priorities. I am especially talking about governmental donors (and their intermediaries) who engage in unfair trade, loan schemes, etc. (at best) and theft of resources (war and colonialism) and then “donate” back a SMALL percentage of their profits, but do so in a way that is controlling for their own interests. I’m sorry to be so blunt and be risked written off as a radical, but here in Palestine, the truth about neocolonialism through “aid” becomes more clear to me everyday. I think we need to face this!

Pingback: June 2012 News « The Fruition Coalition

Hi Akhila. Good article. I’m always surprised at how often when I argue with my friends and colleagues using for the phrase “for members of the privileged elite LIKE US”, the amount of umbrage taken, and the rebukes I receive in return. But it’s just a social fact.

I was asked today whether there were any agencies or programs which follow unconditionally the leadership of the “beneficiaries”. I did manage to think of four. So maybe the tide turns slowly.

Jennifer, what I find troublesome about the cliche that Akhila is “going somewhere” is the implicit shadow-side that in our society, other people aren’t going anywhere. I’ll feel more comfortable when we stop promoting lists of “30 under 30” and “next generation of leaders”, and promote everyone, equally.

Do you know the Jewish tradition of the Tzadikim Nistarim? The tradition holds that there are at any time just 36 virtuous persons who, by their very existence, stop the world from being destroyed. The key is: no-one knows who they are, not even themselves. And as a result, who knows: even you might be one of them.

That’s the kind of leadership paradigm I’d like to see :-).