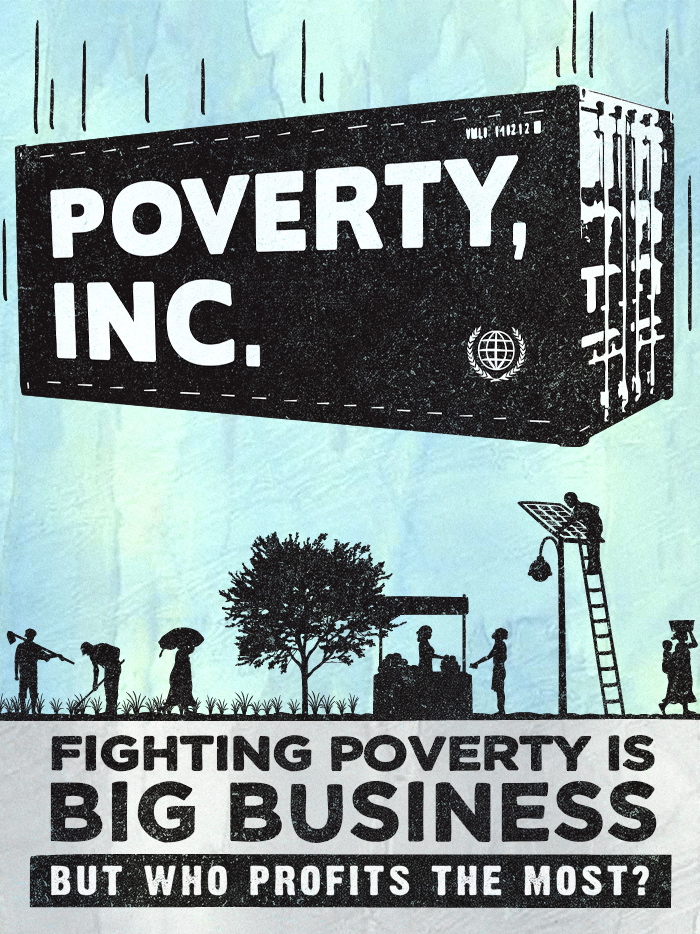

I went to a screening of Poverty, Inc. on Sunday night at Busboys & Poets in DC, always keen to see a film that has the potential to help us in global development ask the deeper questions. Based on “200 interviews in 20 countries,” Poverty, Inc.’s producers stated that they intended “to help redeem charity” with the film, which covers everything from ODA to global trade systems to international adoption to corruption to second-hand clothes imports to rule of law to celebrity aid to social enterprise to neocolonialism.

I went to a screening of Poverty, Inc. on Sunday night at Busboys & Poets in DC, always keen to see a film that has the potential to help us in global development ask the deeper questions. Based on “200 interviews in 20 countries,” Poverty, Inc.’s producers stated that they intended “to help redeem charity” with the film, which covers everything from ODA to global trade systems to international adoption to corruption to second-hand clothes imports to rule of law to celebrity aid to social enterprise to neocolonialism.

In other words, a lot. The question became – is it too much to cover in one film?

As a feature-length documentary, Poverty, Inc. lacks a narrative arc like that found in Stand Up Planet or the Emmy-award winner, Good Fortune, or the more bite-sized, dialogue-friendly format of the film series, Beyond Good Intentions.

The filmmakers managed to get lots of “big” interviews with respected thinkers like Ghanaians Herman Chinery-Hesse and George Ayittey, as well as controversial figures Muhammad Yunus and Paul Kagame. (As occurs all too often, the number of women included was not proportional, though the filmmakers attempted to make screen time equal.) The filmmakers also managed to include some important stories, such as how Haiti solar street lamp-manufacturer Enersa was directly hurt following the influx of solar energy by international NGOs following the 2012 earthquake. These useful illustrations of how international efforts can be well-intended but ill-conceived were peppered throughout the film.

Where filmmakers fell short was in their analysis of ODA, which for most lay people could reinforce the misconception that most development aid is provided directly to foreign governments. Oxfam America’s Foreign Aid 101 publication offers:

“In 2013, only 14.3 percent of USAID mission funds were awarded directly to local institutions, which include host country government agencies, private-sector firms, and local NGOs. The US government provides poverty-reducing development aid through multiple channels, but generally through US-based government contractors and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and also through regional and multilateral organizations.”

While filmmakers included interviews of former NGO staff and aid workers, who eloquently described the problems they encountered while within the aid system, they didn’t include current staff of international agencies. This balance was necessary given that there were Machiavellian and neo-colonial criticisms being offered up throughout the film. This approach made for some great sound bites, but didn’t offer that much insight into how the system actually works. They also failed to discuss the distinct, yet blurry relationship between humanitarian response and longer-term development aid.

Of course the filmmakers’ point of view is clear that the current aid system doesn’t work. A key problem, however, is that they don’t offer much more direction than a photo montage accompanied by peppy music at the end that implicitly encourages viewers to support entrepreneurs in the developing world.

Also, while the filmmakers questioned the aid delivery system, they did not offer the same level of questioning of the global capitalist system and the corporate shareholders that directly benefit from the cheap labor, exploited natural resources, and growing markets in the Global South. To level a critique of the aid system at this level at least warrants an inquiry into the economic inequality and financial realities that shape the wider systems in which international agencies and NGOs work.

A lack of a clear direction (or even options) going forward was apparent to more than just me. During the Q&A following the screening, a gentleman asked if he should still be giving his monthly donations to an international NGO that focuses on clean water. I could tell that he now considered himself more confused than committed to changing the system or finding new ways to channel his hard-earned money. I imagine many other individual donors to international NGOs, who before felt they were “doing something” by giving money, could feel the same way after watching the film.

If you’re looking for a serious, yet somewhat cursory treatment of many of the big issues surrounding aid effectiveness, go ahead and take a look at Poverty, Inc. As someone entrenched in aid critiques, my head was swimming after the film, trying to make sense of everything that was included and how it could be useful to the discourse. That said, there’s a lot in it up for discussion in our sector, and if this film is meant to spur conversation, there’s lots to chew on.

There’s many more global impact films – especially those that highlight local leaders’ fight for rights and accountability – available for you when you want to go deeper and get a better picture of everyday people’s lives, both inside and outside the aid system.

“Everything has been thought of before; the task is to think of it again.” ~Goethe

***

Related Posts

“The Samaritans”: Why are some laughing? Some offended?

PBS Documentary on Aid Shines a Light (and wins an Emmy!)

How many aid workers does it take to screw in a lightbulb?

We want development…but at what cost?

More on “Social Impact Media Awards”

Speaking of… @kenyanpundit explains why Africa can’t entrepreneur itself out of its basic problems http://qz.com/502149 via @qzafrica