A guest post by Tori Dietel Hopps* and Andy Bryant**

Tory: After 25 years of fundraising and playing leadership roles in a variety of nonprofit organizations, I was given an opportunity to work on the funding side of the sector in 2007.

“Wow, what a dream come true!” many of my colleagues said. But I found myself having nightmares about becoming the kind of funder I had tried to avoid for years, and that concern has influenced how the team at Dietel Partners approaches our work.

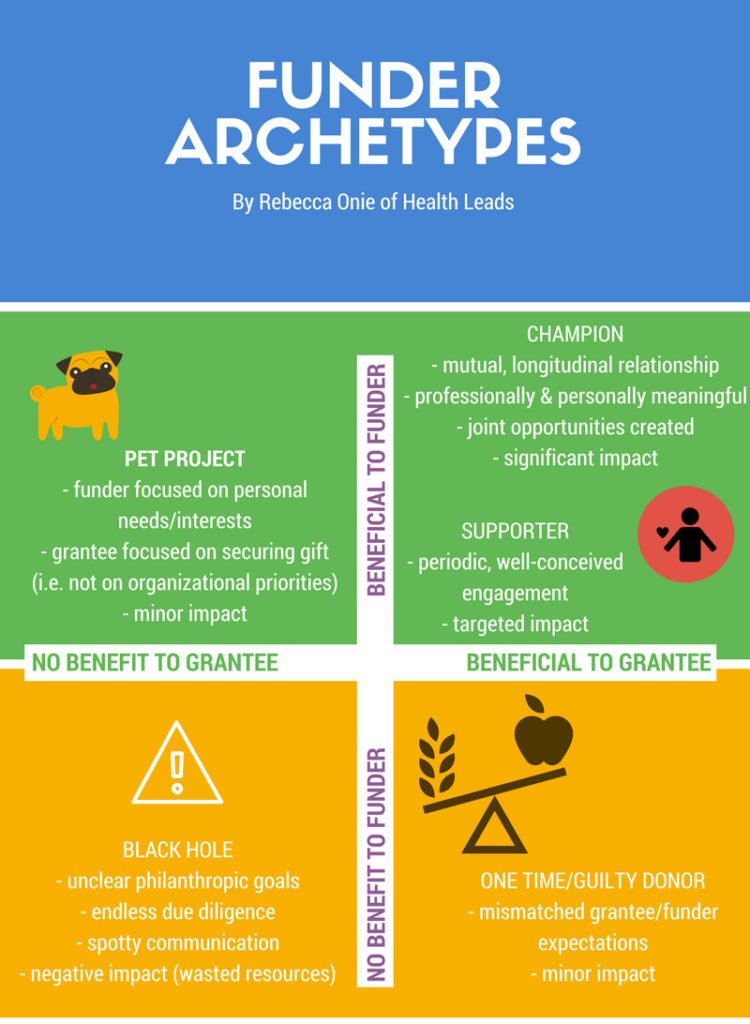

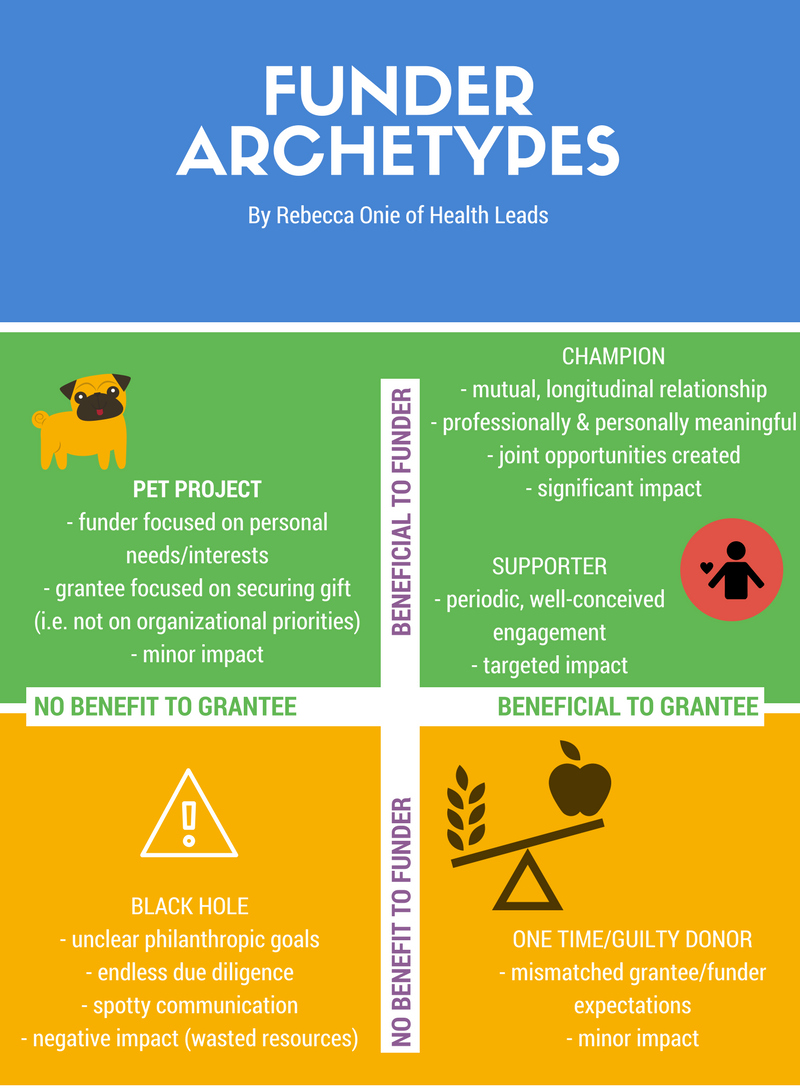

Funders have been categorized in many different ways over the years. When I discovered the simple Funder Archetype matrix (see graphic below), developed by our grantee partner Rebecca Onie of Health Leads, I knew it was the Black Hole Funder that had been haunting my dreams.

The Black Hole Funder typically has the following traits: lacks clarity about their goals, requires an inordinate amount of time from prospective grantees to prove their “worthiness,” is inconsistent at best with communication, and has a lengthy and opaque decision making process. Thankfully, we’ve met some similarly-minded colleagues over the years who are also working hard to avoid the Black Hole moniker.

The Black Hole Funder typically has the following traits: lacks clarity about their goals, requires an inordinate amount of time from prospective grantees to prove their “worthiness,” is inconsistent at best with communication, and has a lengthy and opaque decision making process. Thankfully, we’ve met some similarly-minded colleagues over the years who are also working hard to avoid the Black Hole moniker.

As soon as we began talking with the team at Segal Family Foundation, we knew we had found kindred spirits. Though Dietel Partners (DP) and Segal Family Foundation (SFF) are, in many ways, very different organizations with different foci, we fundamentally agree on an approach to philanthropy that requires us to be extremely attentive to the needs of grantee partners working on the issues that our clients/donors care about. We believe that it is incumbent upon us to be proactive and deploy resources far beyond grant dollars to help advance the work of our partner organizations. Some people call this type of approach “grantee-centric” and here we attempt to shine some light on what that actually looks like in practice.

What does it mean to be “grantee-centric”?

Rather than offering an overused, vague definition, here some characteristics of our approaches:

- Helpful. We believe it is our job to be of service to our grantee partners and to be as nimble, flexible, and labor-saving as possible.

- Trust-based. Mutual trust and respect must be earned by funders and continually nurtured. Funders must take some measured leaps of faith.

- Risk tolerant. These leaps of faith don’t happen without risk, and there are many contributing factors to success and failure, several of which cannot be foreseen. A safe bet isn’t usually the best use of our funding.

- Pro-active. It is our responsibility to be constantly thinking about what we can bring to our partners’ success.

- Responsive. We commit to communicating and acting in a timely manner.

- Curious. We recognize that we sit at the nexus of learning from a wide variety of actors in our sector, and it is incumbent on us to identify patterns and share knowledge widely.

- Collaborative. The challenges we seek to address will not be solved by single players. We have a role to play in seeding, fostering, and participating in partnerships and coalitions.

- Energetic. We must be dependable and passionate advocates for the people we serve.

- Celebratory. We believe we must celebrate the people who do the work on the ground every day.

Next we offer two examples of how we incorporate these values into our operations.

Side car funds and service providers

Tory: Prior to the 2008 financial crisis, Dietel Partners was managing several philanthropic portfolios for clients that were dedicated to issues of social justice writ large. As the economic crisis unfolded, several prominent human rights funders were decimated and unable to continue their funding commitments. We knew that a number of our grantee partners were in emergency mode and deserved a swift response. Our response had to take into consideration both the emotional well-being of the leaders and their teams, as well as the financial reality they were confronting.

Our response was to turn to our clients and suggest that they set up an Emergency Side Car Fund to their existing grantmaking portfolios. The Side Car Fund would be dedicated to provide immediate emergency assistance to grantee partner organizations that were already approved and in their grant portfolios. Eighty percent of our clients agreed and dedicated 5% of their annual charitable budget to establish such a fund.

The deployment of these funds was left to us, the advisors, who were regularly in touch with grantee partners. What ensued were timely and frank conversations with grantee partners about the troubles they were facing. By giving us the leeway to make quick decisions, we could save already stressed organizations from jumping through unnecessary hoops to receive support. Emergency grants (averaging $25k or less), which were quickly deployed within 48 hours, had many positive results. They fostered extremely candid conversations, enabled joint problem-solving, and provided financial and stress relief to our grantee partners. In the long run, this attempt to be as responsive as possible cultivated deeply-trusting relationships with our grantee partners.

After the economic crisis calmed down, Dietel Partners was convinced we had hit upon a powerful tool in our work. We recommended that our clients convert the Emergency Side Car Funds into Opportunity Side Car Funds for unanticipated moments of opportunity and time-sensitive capacity building needs for grantee organizations already in our client’s grant portfolios.

Having funds to deploy rapidly for a merger exploration, an advocacy moment, a strategic hire, a technology fix, or an unexpected event enabled us to engage in probing and thoughtful conversations and build trust. We found grantee partners were more likely to put issues on the table and more willing to think creatively if we could act quickly on our end.

Since 2012, 25% of the organizations in our clients’ portfolios have benefited from these Opportunity Side Car Funds. To date, the most common use of funds has been for time- sensitive talent recruitment, opportune professional development, urgently-needed technology and communications upgrades, expeditious strategic and business planning, pressing board governance issues, and rapidly convening partners.

“The opportunity to work on a policy initiative came up quickly. But finding a philanthropic partner who is willing to be the first money in on a project like this—and finding one who is able to move as quickly as we need to in order to take full advantage of the opportunity in front of us—is a challenge. Thank you for being there for us as a thought partner on this, and for making it possible for us to take this leap. I am confident this is an investment that will pay off for years to come.” –Curt Ellis, CEO, FoodCorps

Roughly 50% of the Opportunity Sidecar Funds that have been deployed has necessitated that our grantee partners bring in outside expertise. While the funding is important, it takes time to figure out what kind of service and whether they are a good fit. We decided another way we could be of service was to save our grantees time and energy in seeking excellent service providers. We reached out to our network of grantees, other funders, and colleagues to compile a list of service providers that people recommended. (It is important to note that Dietel Partners does not make funding contingent upon use of one of the listed resources.) Grantee partners have found that this list is indeed a helpful jumping-off point when they are looking for external help, saving them valuable time in the search process.

Local solutions are the best solutions

Andy: For me, social justice is simply the process of pushing agency—choice—as close to the people as possible. As a grantmaker, this means giving up some of our own agency if we want to meaningfully tackle challenges facing marginalized people.

When Dedo Baranshamaje, a young Burundian with ideas so big they were matched only by his infectious charisma, joined our team, he created our Social Impact Incubator—the riskiest and most rewarding piece of philanthropy we have attempted.

In Burundi, in the summer of 2011 when the incubator started, there was a vacuum where a robust civil society might live. After years of colonial rule, civil war, coups, corruption, and poverty, there existed distrust, back-biting, and little incentive to collaborate among Burundian non-profits. Many of the funders we met expressed a desire to fund local organizations, but they were frustrated by their attempts to find “trustworthy” leaders or “sophisticated” programs. Local non-profit leaders, in turn, expressed resentment that funders forced them to become mercenary implementing partners, hitched to whatever aid trend du jour was foisted upon them.

In this fragmented civil society space in Burundi, our team saw an opportunity to help repair decades-old divisions keeping Burundians from accessing basic health and education services by creating something new. If we could identify and nurture local visionaries (“rockstars” in our parlance), perhaps we could contribute to sustainable change and build our own portfolio of partners in the process.

We would need to take some big risks. Our newly-minted Social Impact Incubator would take a lot of our time, bring attention from government that we wouldn’t normally seek, and be an uncomfortably-ambitious undertaking for our team. But we needed to be responsive and helpful, so we brought together an advisory committee, surveyed as many local informants as we could find, and advertised the incubator opportunity in the press. In essence, we took a measured leap of faith. Over the course of three years (2013-15), over 60 Burundian grassroots organizations participated in the Incubator.

Much of the incubator itself was not particularly new or innovative: a lot of classroom learning, one-on-one coaching, and polishing of participants’ models. Where we found our greatest success, however, was in promoting the participants’ work with other funders. They needed a mechanism of identifying and validating local organizations. The same bilaterals and international NGOs that decried the lack of local visionaries were eager to meet our incubator participants!

The other area where we witnessed great success was within the participant cohort as sharing classrooms, competitions, and cocktails began to erode much of the distrust that had existed between them. The results were startling to us, especially as our foremost desired outcome at the onset was simply to do no harm. Unfortunately, political unrest forced our team to leave Burundi in late 2015, but since then we have seen:

- A 10:1 Return on Investment: We have documented several million dollars in new and mostly unrestricted funding flowing to participants as a result of connections they made within the Social Impact Incubator (against an annual budget of less than $100,000).

- Changes in Civil Society: Over time, we witnessed funders and INGOs change their funding practices, giving more unrestricted funding. We saw collaboration occur as both CARE Burundi and ActionAid signed on as co-sponsors of the Incubator. CARE has since received funding to continue the incubator in our stead. Additionally, many of the incubator participants continue to meet on their own and regularly report back on their activities to our team. In fact, several have collaborated on jointly-funded projects.

- Replication: Since leaving Burundi, we reconstituted the Social Impact Incubator in Malawi, recently graduating our first class of 25 participants. We are in the process of creating a replication package for sharing, and we are talking with several funders and INGOs about replicating the project elsewhere in Africa.

In conclusion: Avoiding the black hole moniker

Andy: Both Dietel Partners and Segal Family Foundation have been fortunate to stand on the shoulders of like-minded funders, brave grantees, and each other. In the same manner in which we encourage and underwrite collaboration among our grantees, we have committed to engage our peers in the funder space through affinity groups, rich individual relationships, and sharing of information.

Tory: Finally, our joint curiosity leads us to continually look for patterns across the wide variety of grantmaking portfolios we manage. Gaining greater insight into the challenges grantee partners face inspires us to be on the lookout for how to connect our partners with others in a variety of fields who have dealt with similar issues. Increasingly, we hear that the time we spend on making key introductions for joint learning and problem-solving saves our partners time and money and builds bonds across a broader sector.

Andy: Our shared philosophy to be grantee-centric made both of our organizations look for opportunities when faced with crisis. From the U.S. financial crisis to a broken civil society in Burundi, necessity can be the mother of invention. The leaps of faith we took in developing new and risky programs eventually became the norm—pillars of partnership models that put grantees first.

*Tory Dietel Hopps is Managing Partner of Dietel Partners. Dietel Partners guides the experience of giving with customized engagements through a shared family philanthropic office. Dietel Partners seeks to reshape the experience of philanthropy by bridging the interests of philanthropists and change makers to build a better world.

**Andy Bryant is the Executive Director of Segal Family Foundation. SFF partners with outstanding organizations improving the well-being of communities across Sub-Saharan Africa. Andy believes that local solutions are the best solutions.

Related Posts

Philanthropists, nonprofits need you to be brave

Why I wrote about “smart risks” in philanthropy and why I would frame it differently now

A new kind of donor: 4 things they do differently

Getting money to the ground, directly

Actually, it was my capacity that needed to be built

3 ideas for making locally-led aid responses a reality

Is there a better way for indigenous and international NGOs to work together?

Do grassroots organizations in poor countries have an image problem?

How to build strong relationships with grassroots organizations, Part 3 of 3

Great write up- keep posting. Donor shadowed funding streams tend to keep swaying organizational and community needs foci visa – a -vis back and forth development trajectories.